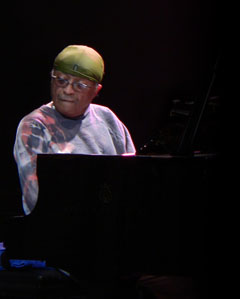

Cecil Taylor

15 November 2004, Royal Festival Hall, London Jazz Festival

Who

decided to squeeze two giants of the avant-garde into a single evening?

Such a decision betrays a niggardliness that verges upon intellectual apostasy.

If the audience is impatient to hear Cecil Taylor then the way the evening

unfolds will only add to their impatience: after Anthony Braxton’s

set and a fairly brief interval, Cecil Taylor does not appear on stage.

Instead Tony Oxley strolls on alone, looking for all the world like a white-haired

Patrick Troughton. After a few adjustments to his drumkit, he begins a lengthy

solo which proves to be a masterly exploration of attack and decay, and

drama. Unexpectedly it quickly becomes clear that he’s accompanying

a prerecorded percussion piece of undeclared provenance. This arrangement

conveys the slightly disorientating impression of viewing two overlaid transparencies

that are not quite synchronised. At the conclusion of his performance, Oxley

nods his head and strolls off the stage.

Still no Taylor. Oxley is succeeded by Bill Dixon whose history with Cecil Taylor goes back at least as far as 1966 when he appeared on the latter’s Blue Note release, Conquistador. Today he’s dressed in smart casual clothing and sports a silver beard. He picks up his trumpet and begins playing into a microphone arranged at waist height and it’s immediately apparent that this highly sensitive microphone has an almighty great echo attached to it. As Dixon spits and puffs down the tubes of his instrument his breath conjures incredible outer space sounds that echo around the auditorium. It’s as out as Sun Ra’s Heliocentric Worlds. His solo is fascinating for the first ten or so minutes until he exchanges trumpets. Unfortunately the remaining five or ten minutes are a redundant reiteration of the first half of his solo until he too departs the stage.

After a couple of lengthy minutes and some disgruntled murmuring from the audience, the great man finally arrives and launches into a characteristic solo: dense, dramatic, worrying at multiple figures successively, reforming them from bar to bar. Such is the vigour with which he delivers and mutates these forms, that there’s the strange impression that his musical shapes are changing in transit between piano and audience. Despite this, there’s a real sense of space, whether it’s implied, negative space or actual micro-pauses. As a result the music never sounds busy or hurried, rather it’s intensely focused. After ten minutes, Oxley and Dixon join Taylor as he continues to play, leaning into the piano with his shoulders and upper body. Taylor’s physicality inevitably finds its analogue in the music and it’s this sense of the corporeal combined with the piano’s fixed musical structure which makes this music, however challenging, more immediately accessible than Anthony Braxton’s preceding set. Dixon appears to play a non-structural part in the music, instead blending and surfing the flow with breaths, moans and echoes. Although the majority of the interaction occurs between Oxley and Taylor, during the course of the piece though there is a strong sense of a whole created by the trio which gradually fuses together, pulls aparts and then recombines. Unfortunately, after 25 minutes Taylor calls time, takes a bow with his colleagues and departs. Despite enthusiastic calls for an encore the trio do not return. The brevity of the set only compounds further the sense of frustration experienced at two great composer-players having to share a single billing.

Still no Taylor. Oxley is succeeded by Bill Dixon whose history with Cecil Taylor goes back at least as far as 1966 when he appeared on the latter’s Blue Note release, Conquistador. Today he’s dressed in smart casual clothing and sports a silver beard. He picks up his trumpet and begins playing into a microphone arranged at waist height and it’s immediately apparent that this highly sensitive microphone has an almighty great echo attached to it. As Dixon spits and puffs down the tubes of his instrument his breath conjures incredible outer space sounds that echo around the auditorium. It’s as out as Sun Ra’s Heliocentric Worlds. His solo is fascinating for the first ten or so minutes until he exchanges trumpets. Unfortunately the remaining five or ten minutes are a redundant reiteration of the first half of his solo until he too departs the stage.

After a couple of lengthy minutes and some disgruntled murmuring from the audience, the great man finally arrives and launches into a characteristic solo: dense, dramatic, worrying at multiple figures successively, reforming them from bar to bar. Such is the vigour with which he delivers and mutates these forms, that there’s the strange impression that his musical shapes are changing in transit between piano and audience. Despite this, there’s a real sense of space, whether it’s implied, negative space or actual micro-pauses. As a result the music never sounds busy or hurried, rather it’s intensely focused. After ten minutes, Oxley and Dixon join Taylor as he continues to play, leaning into the piano with his shoulders and upper body. Taylor’s physicality inevitably finds its analogue in the music and it’s this sense of the corporeal combined with the piano’s fixed musical structure which makes this music, however challenging, more immediately accessible than Anthony Braxton’s preceding set. Dixon appears to play a non-structural part in the music, instead blending and surfing the flow with breaths, moans and echoes. Although the majority of the interaction occurs between Oxley and Taylor, during the course of the piece though there is a strong sense of a whole created by the trio which gradually fuses together, pulls aparts and then recombines. Unfortunately, after 25 minutes Taylor calls time, takes a bow with his colleagues and departs. Despite enthusiastic calls for an encore the trio do not return. The brevity of the set only compounds further the sense of frustration experienced at two great composer-players having to share a single billing.

Colin Buttimer

Published by Me