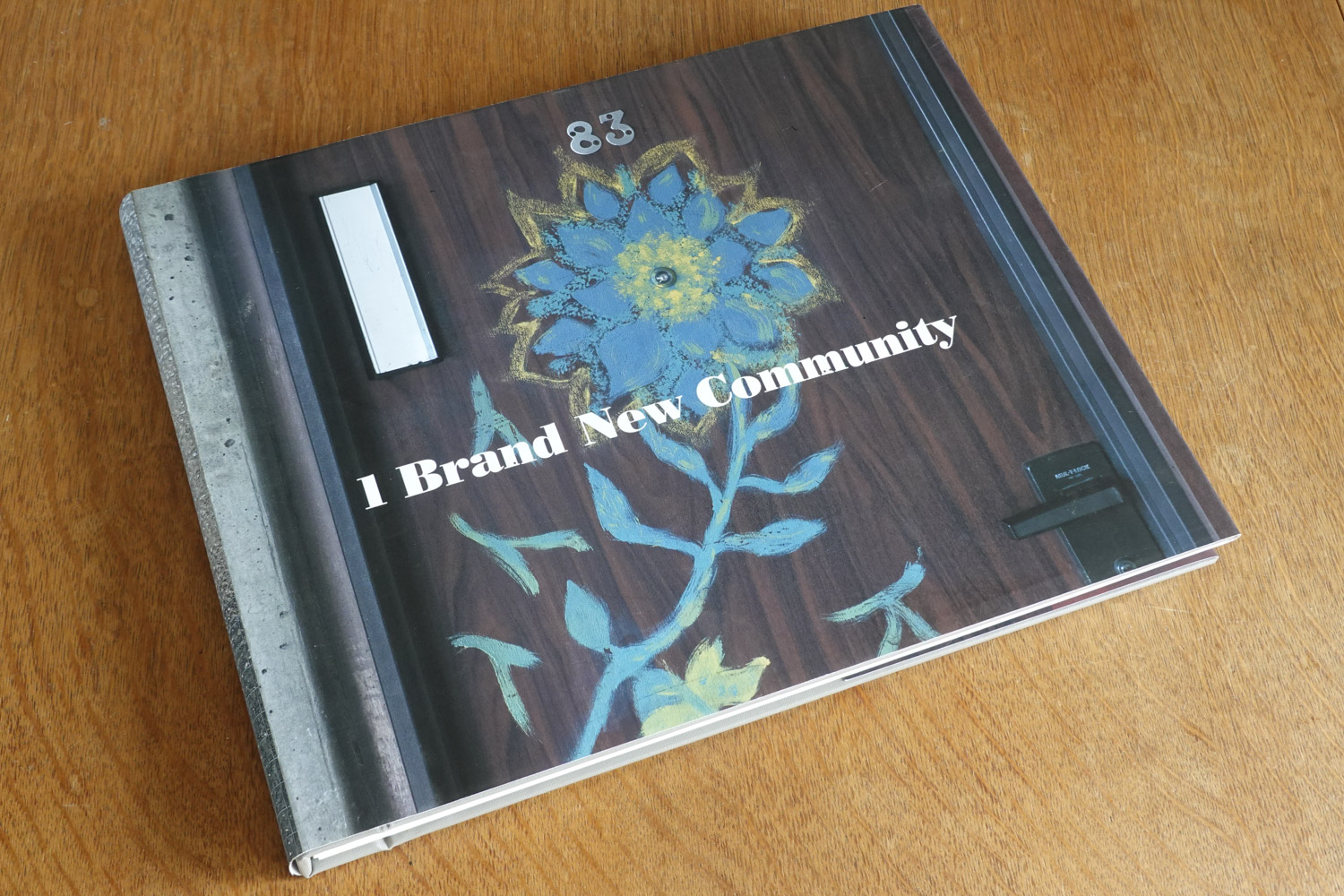

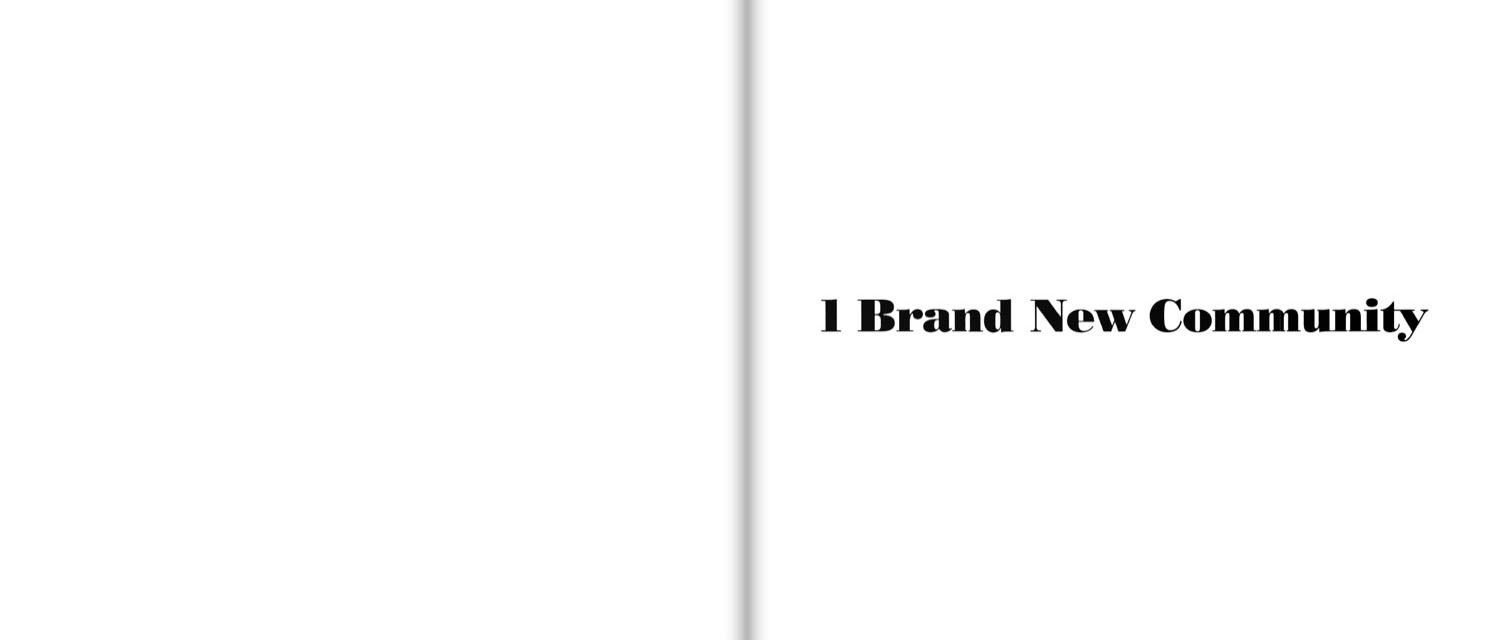

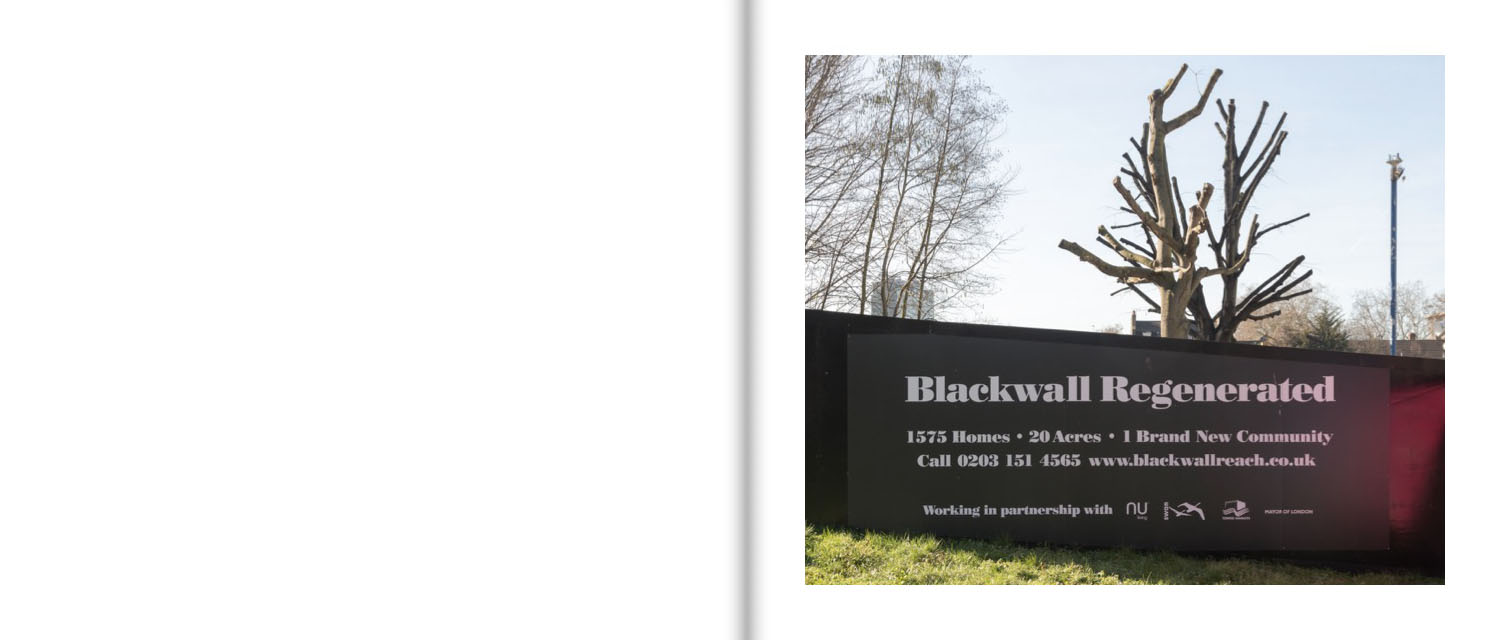

1 Brand New Community

Dimensions: w: 39.7cm, h: 30.3cm

Photographs (59): 2011–2019

Book: 2019

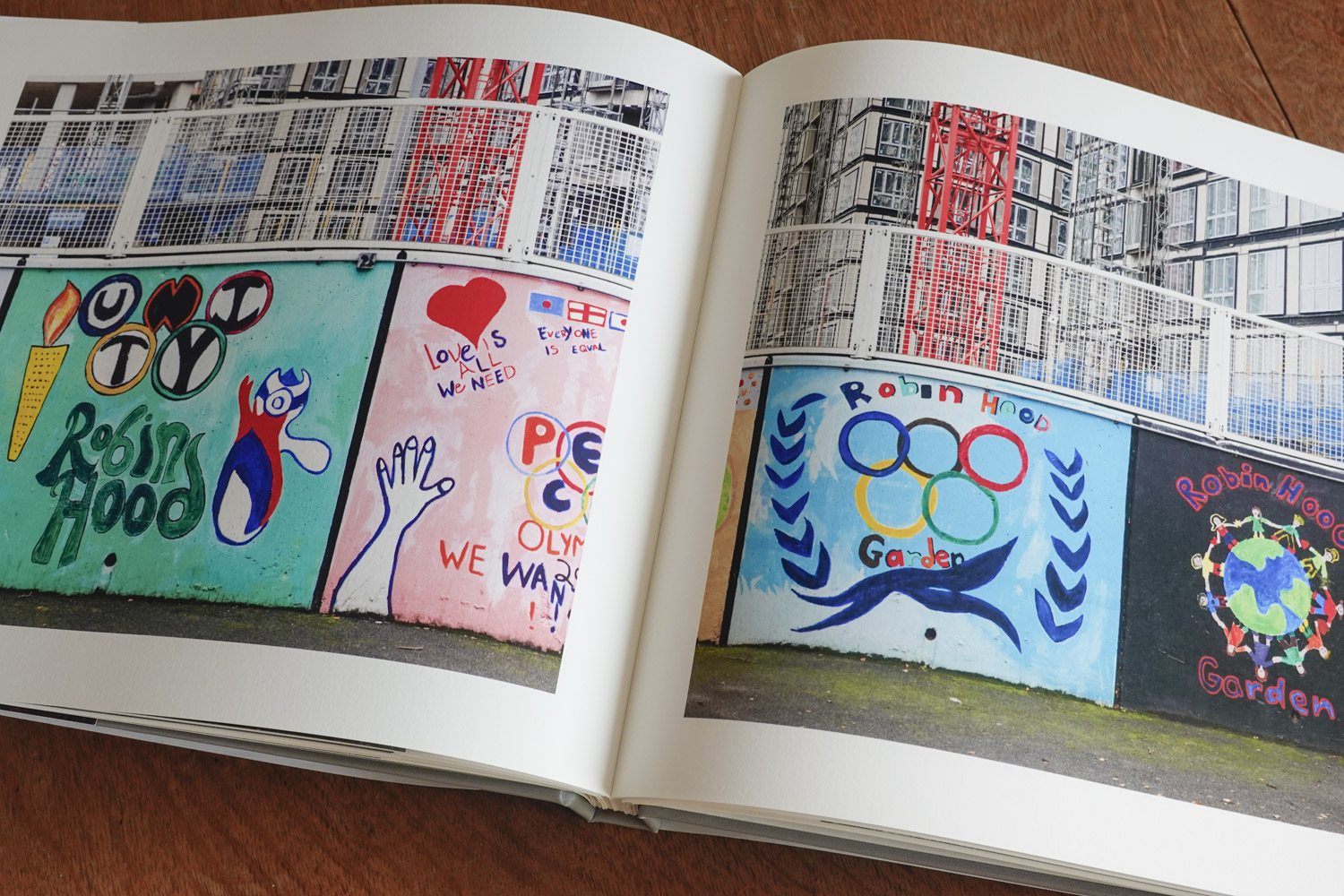

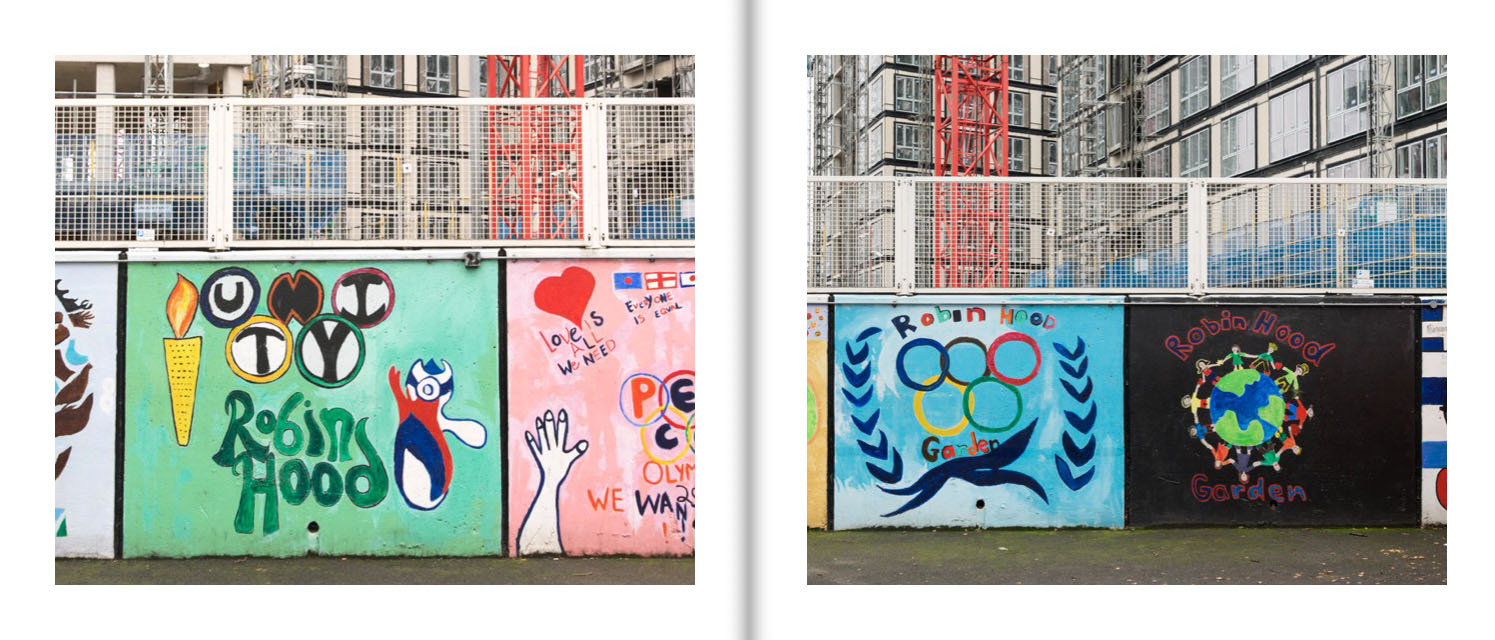

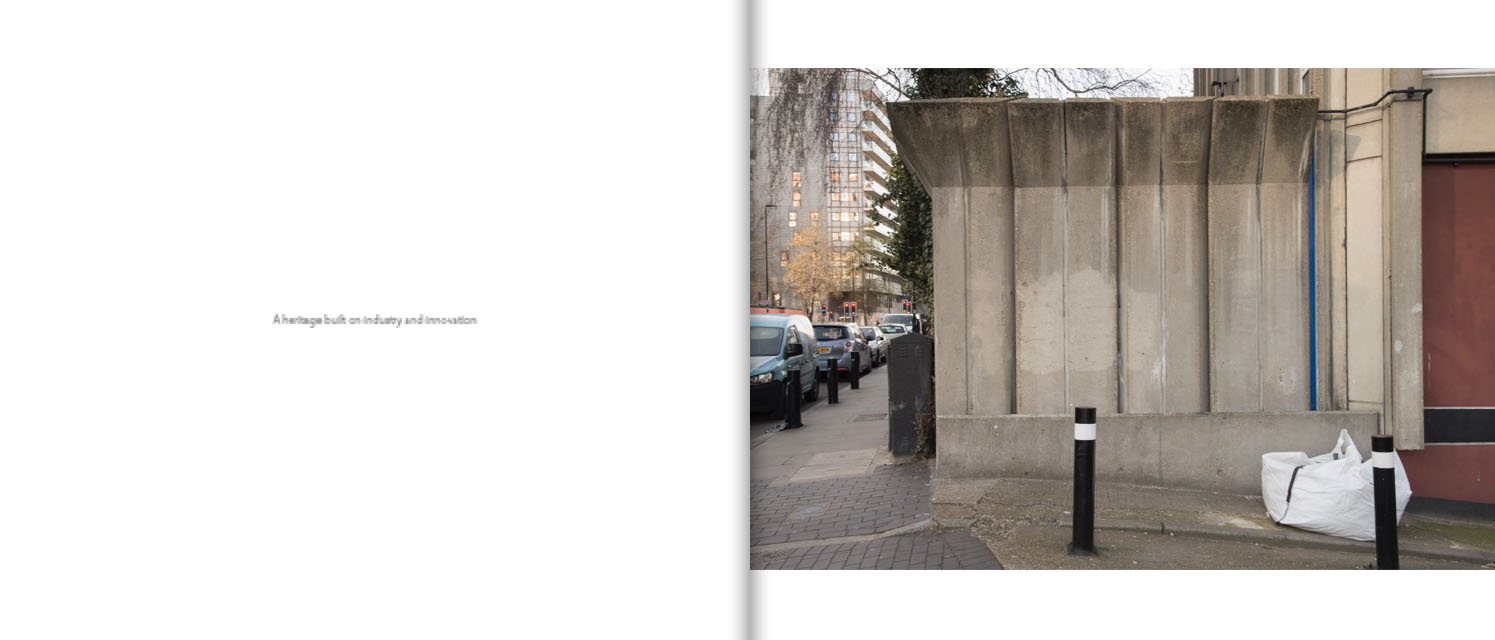

The Robin Hood Gardens estate lies at the nexus of a remarkably broad range of issues including, but not limited to, the funding of the welfare state, neoliberalism, austerity, Right to Buy, the financialisation of housing, the treatment of council tenants and immigrant minorities, urban planning, the social role of architecture, and the politics of cultural preservation.

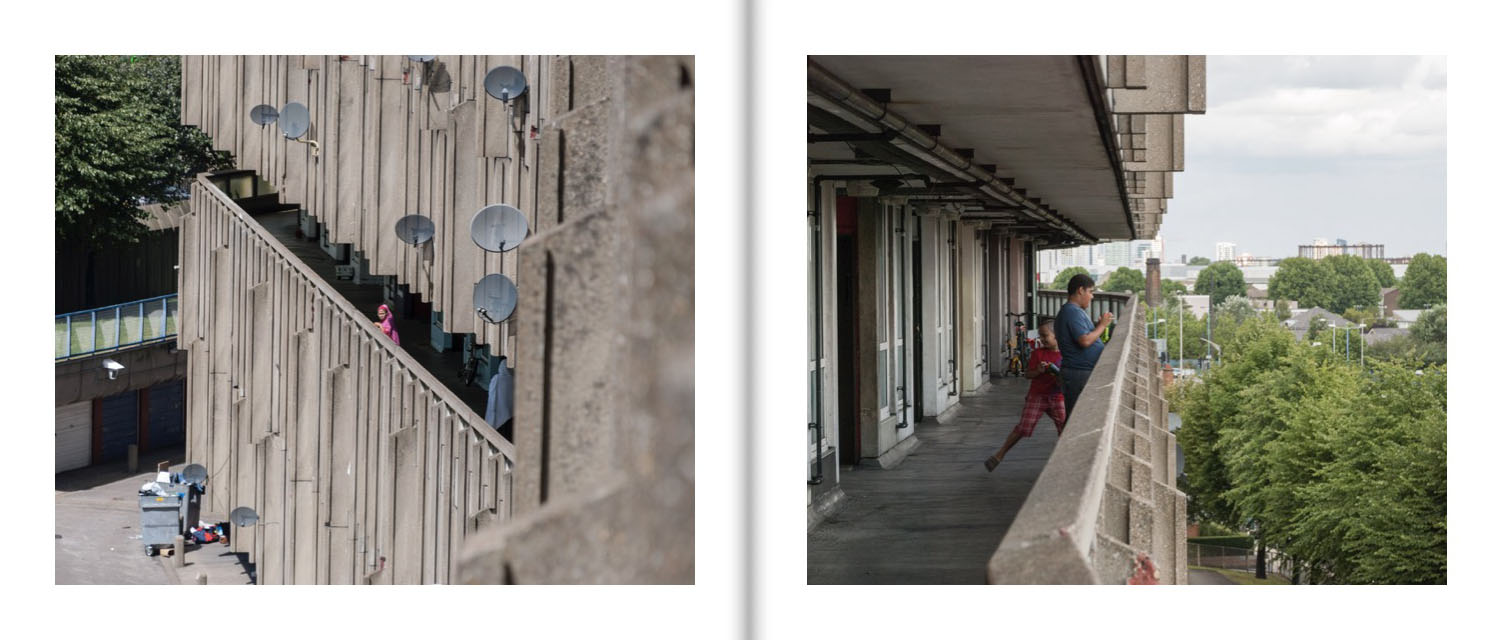

The estate’s fate provokes more questions than it seems possible to answer, and any response is highly contested. Sometimes, though, Alison and Peter Smithsons’ architecture appears to be valued more highly than the residents themselves.

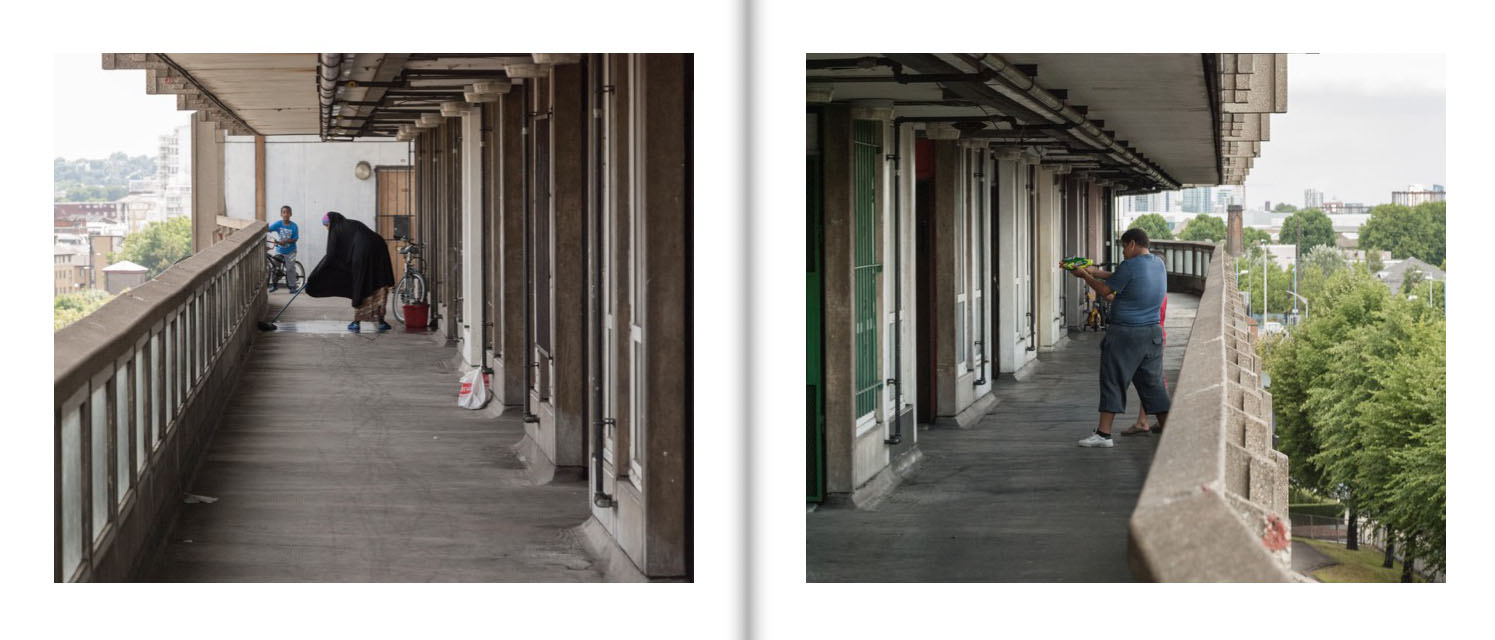

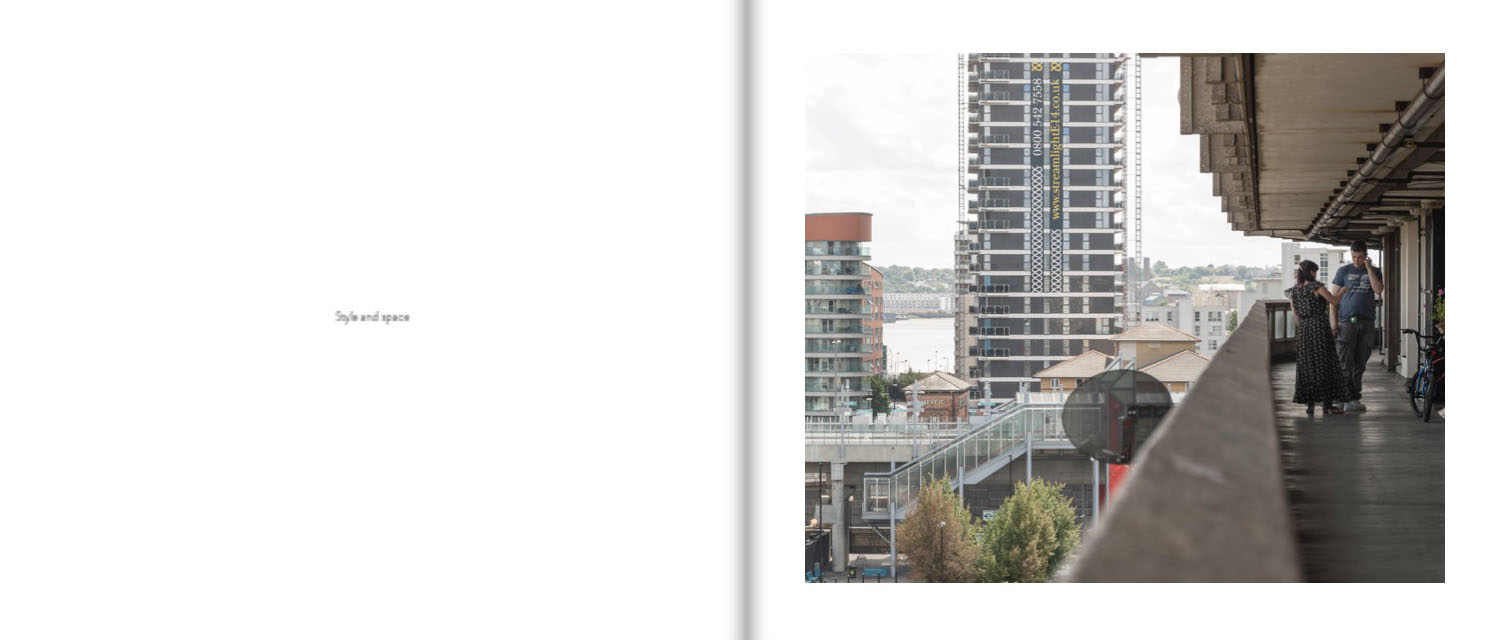

I first visited Robin Hood Gardens in 2011 after reading about the idea of the streets in the sky. I wanted to see whether the dominant, negative perspective on this short-lived endeavour to address the social isolation of high-rise living was locally accurate. Here’s an example of that view from Wikipedia’s entry on High-Rise Building:

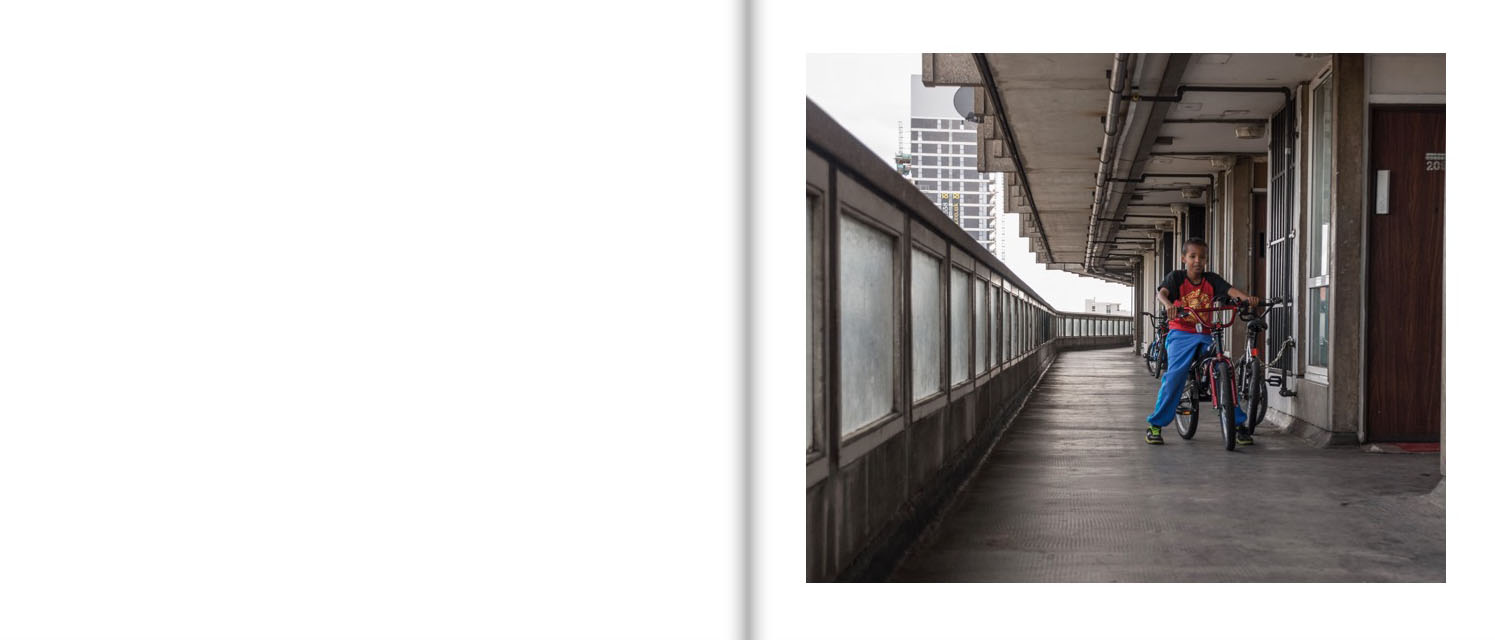

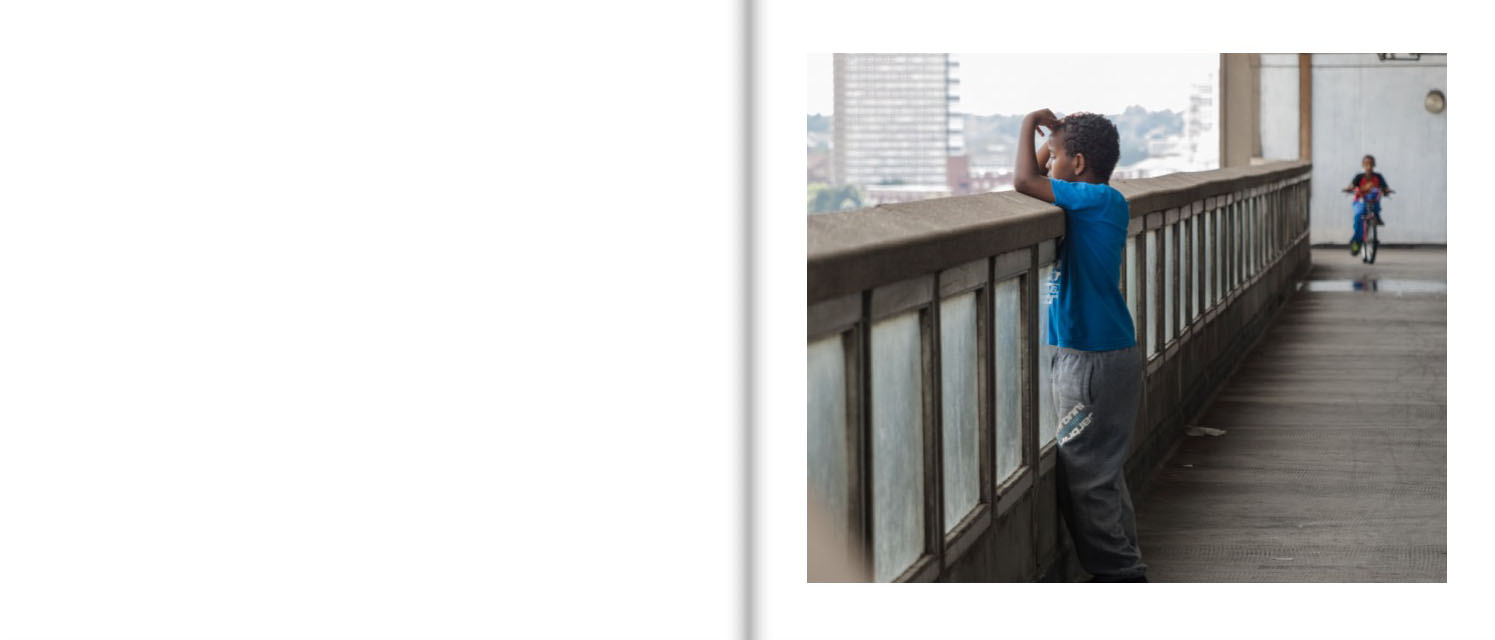

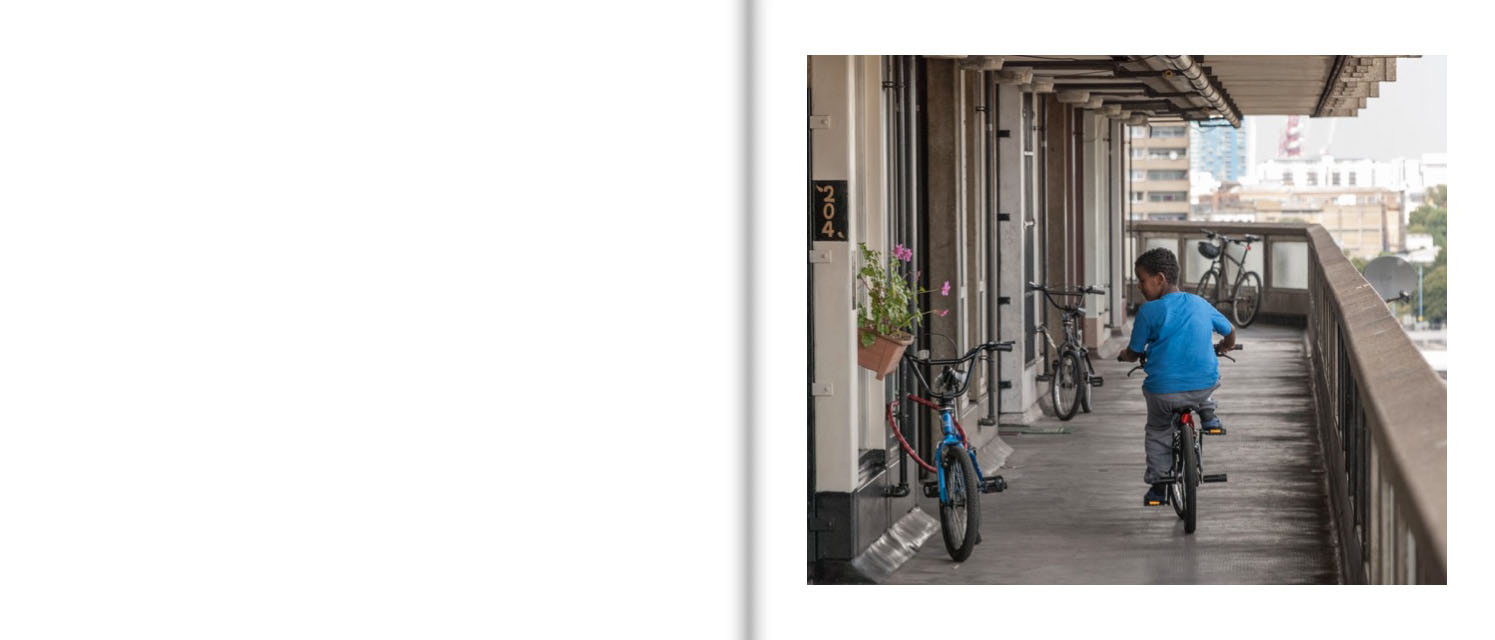

The ideal of Streets in the Sky often did not work in practice. Unlike an actual city street, these walkways were not thoroughfares and often came to a dead end multiple storeys above the ground. They lacked a regular flow of passers-by that could act as a deterrent to crime and disorder. This was the concept of “eyes on the street” described by Jane Jacobs in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Furthermore, the walkways and especially the stairwells could not be seen by anyone elsewhere.

I suspected that architectural design was being blamed for changes in central government and local council policies. Such is the pervasiveness of this view that it is stated as common sense by many poeple. Should buildings be designed to ameliorate the worst effects of a changing political climate? How would that be possible?

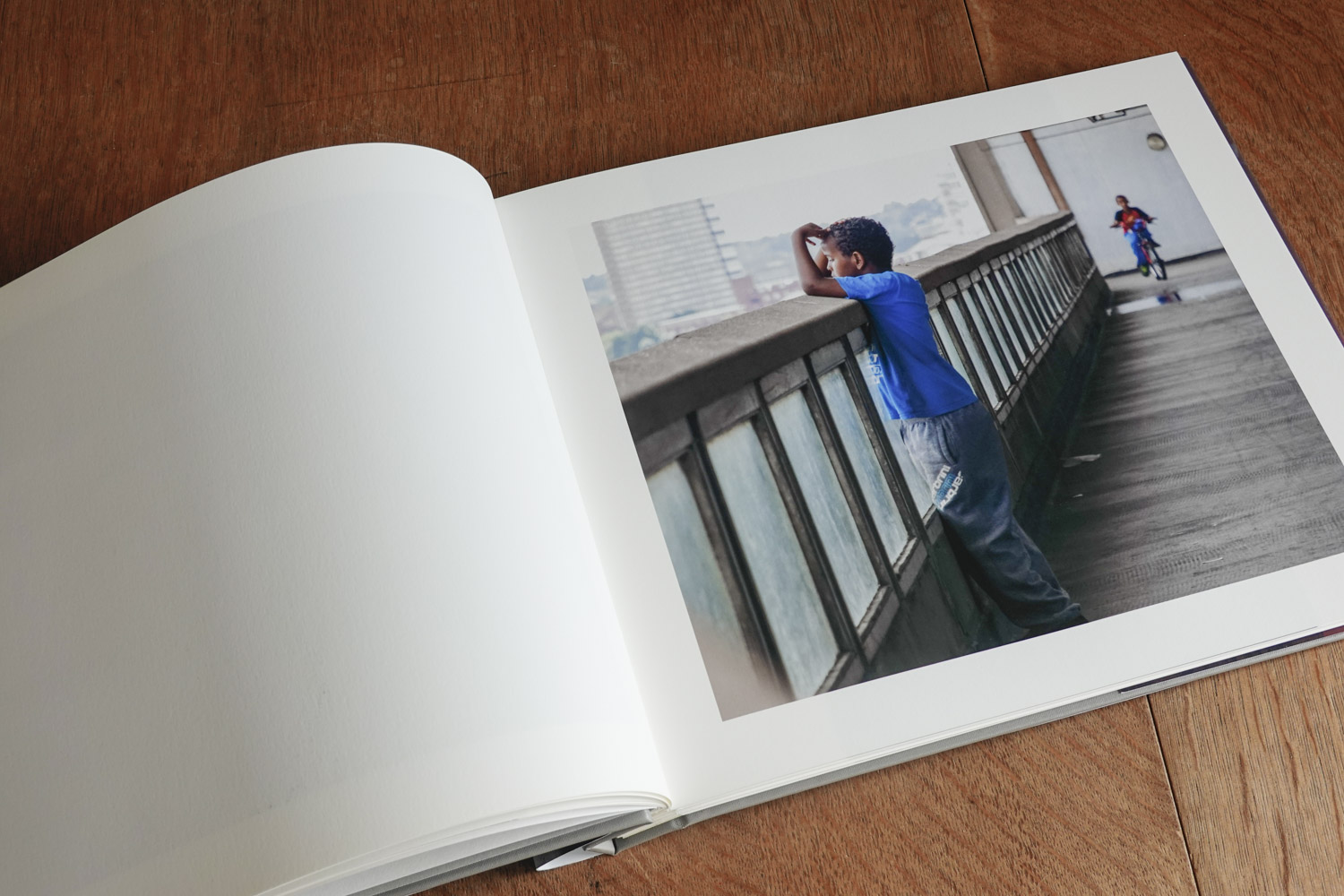

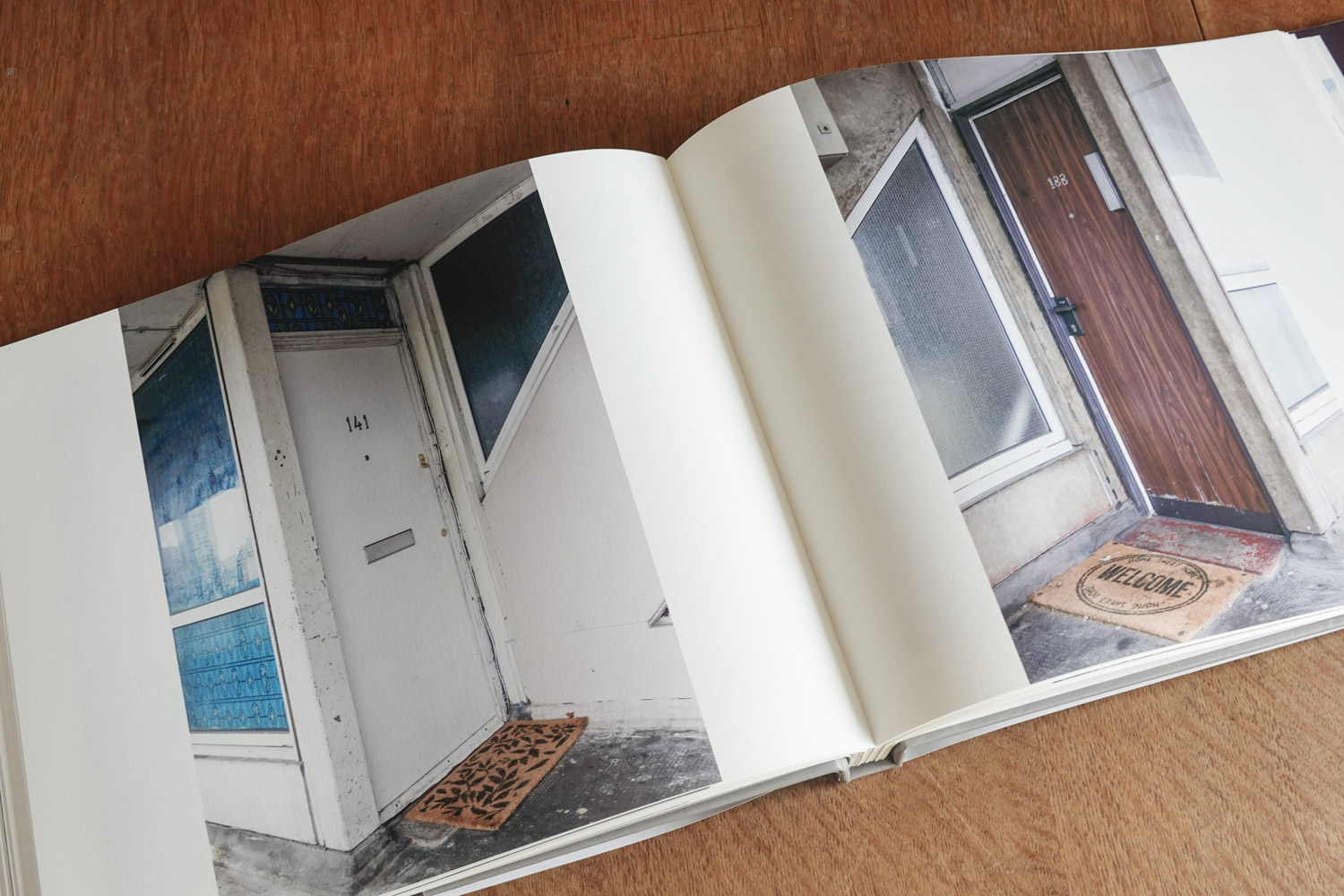

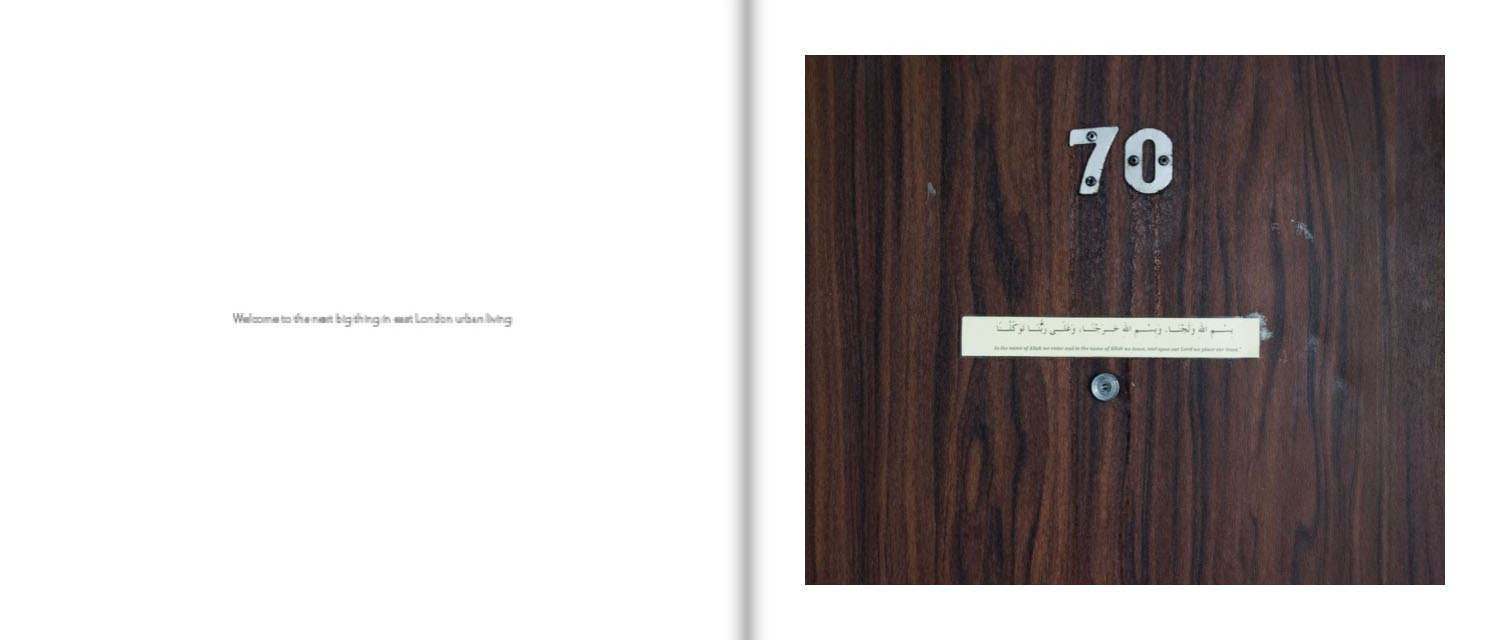

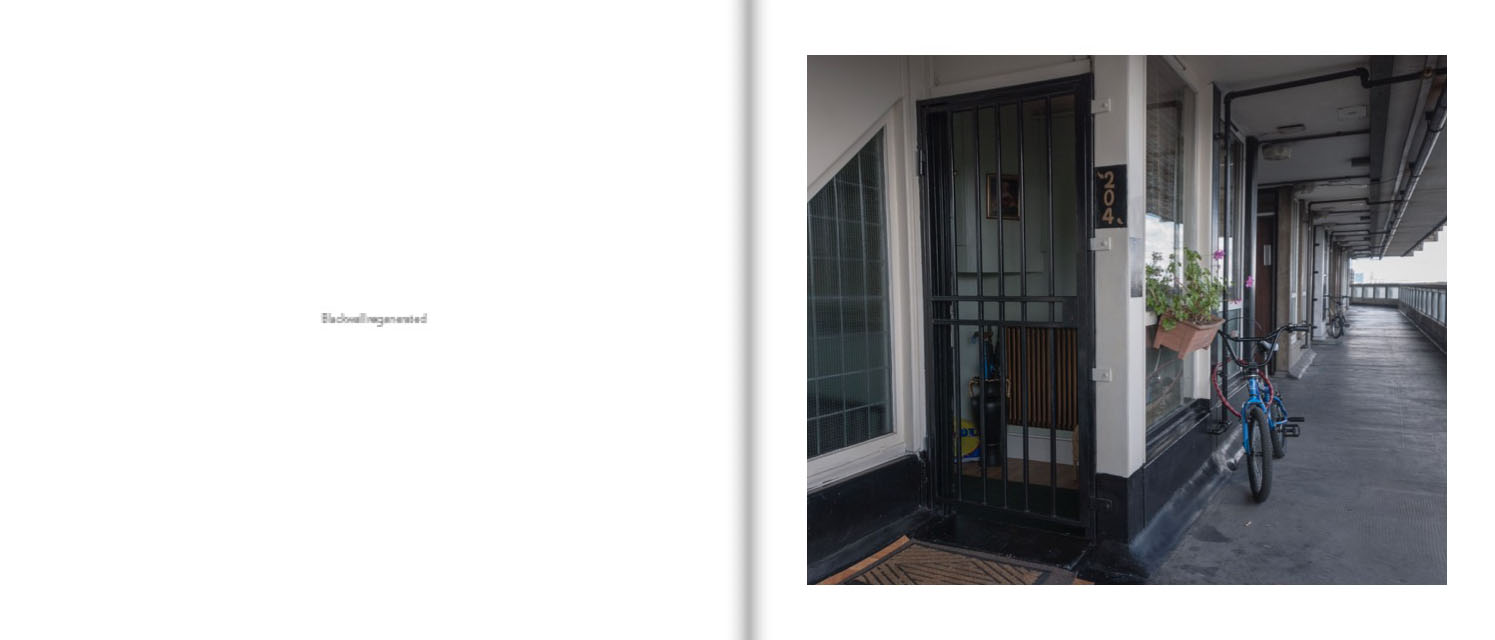

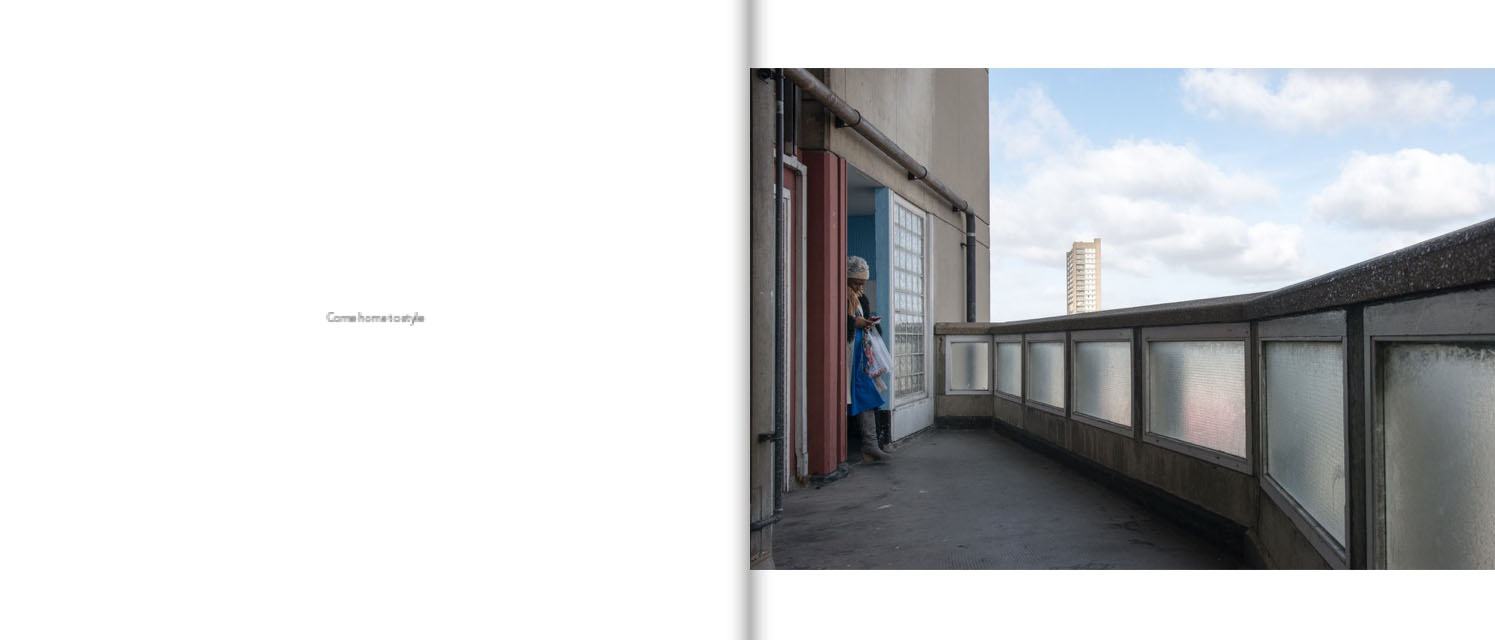

Peter Smithson, clearly somewhat disillusioned when interviewed in the 1990s, might have been cheered by what I saw and photographed:

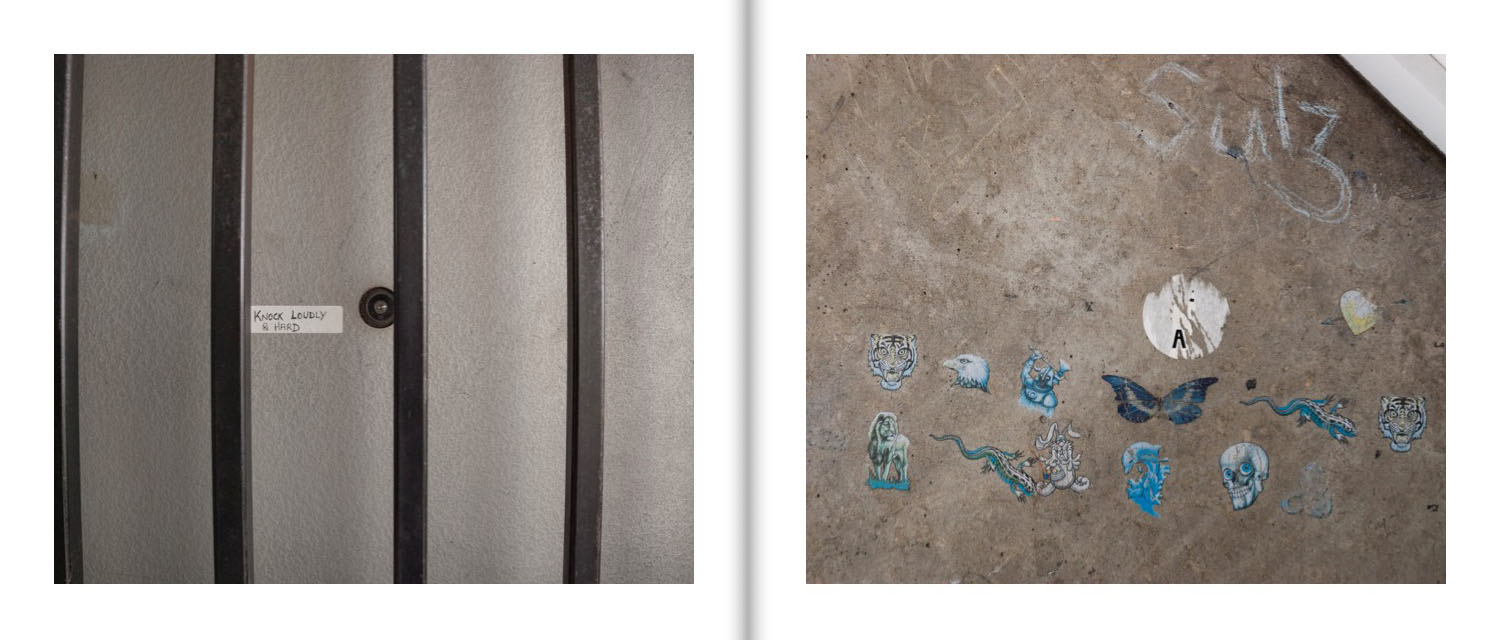

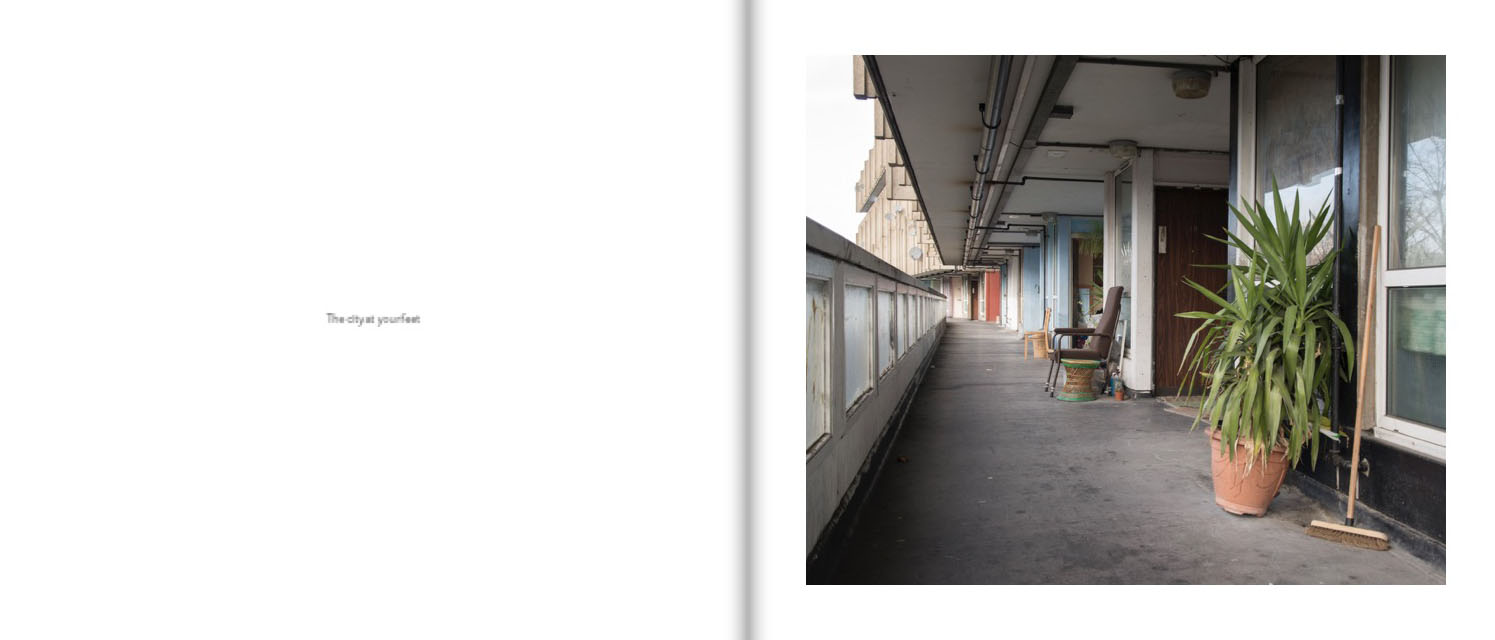

In other places you see doors painted and pot plants outside houses, the minor arts of occupation, which keep the place alive. In Robin Hood you don’t see this because if someone were to put anything out people will break it.

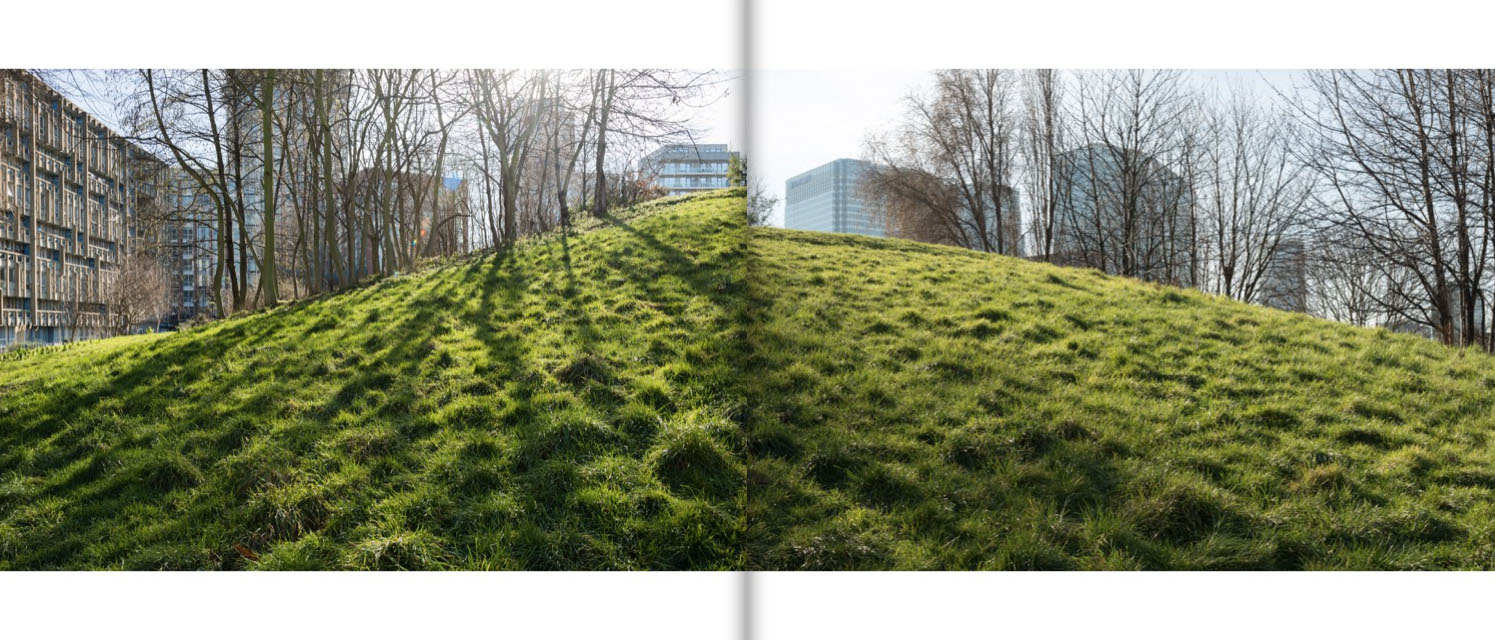

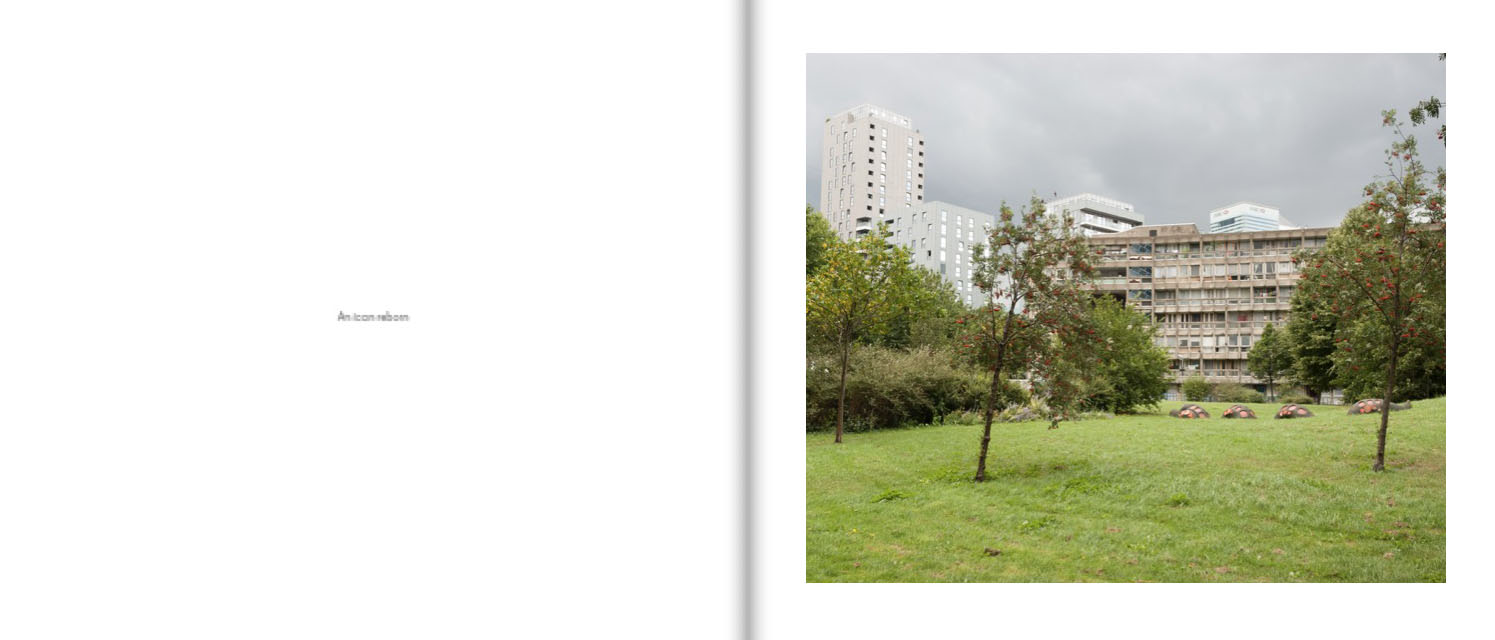

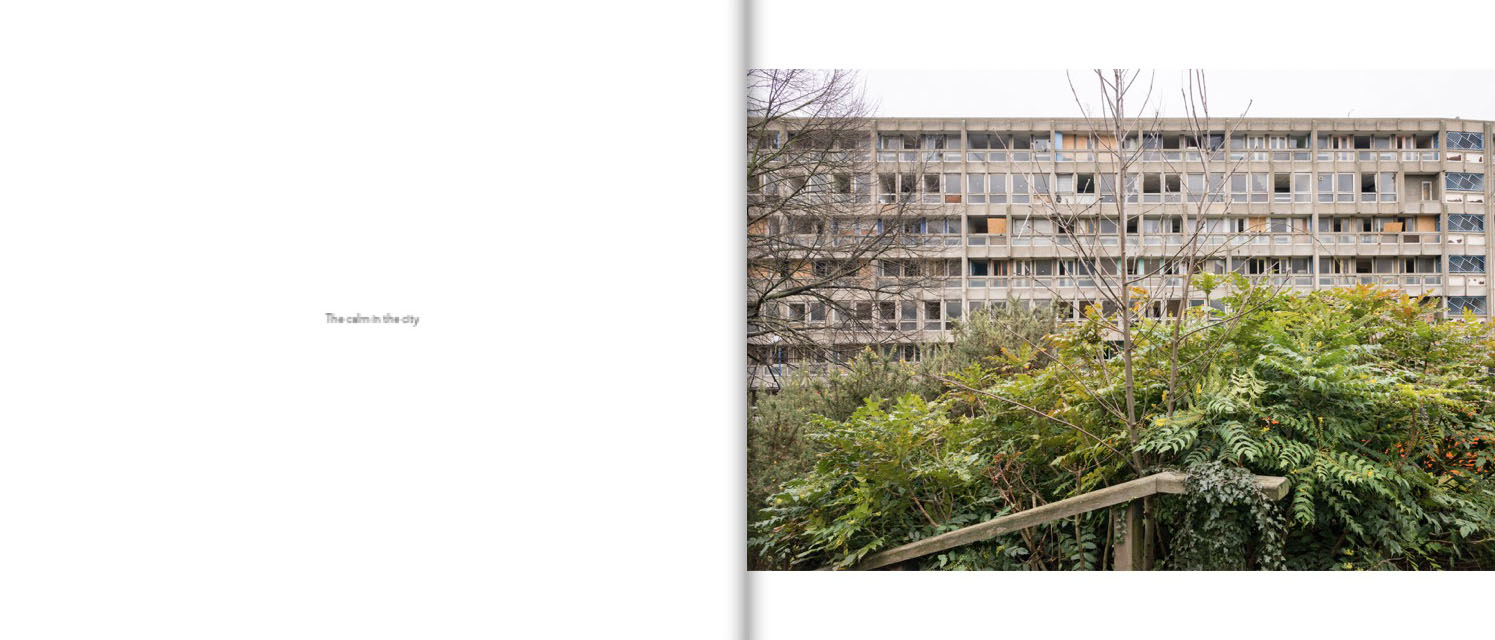

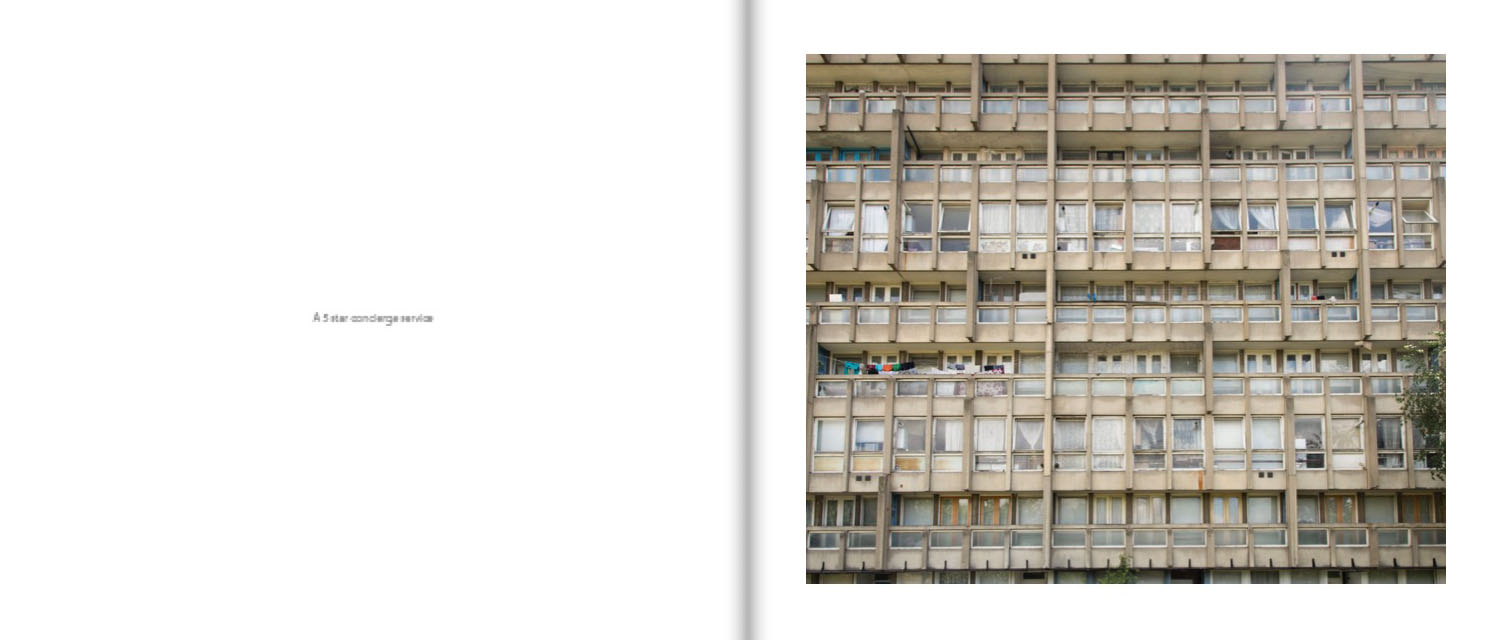

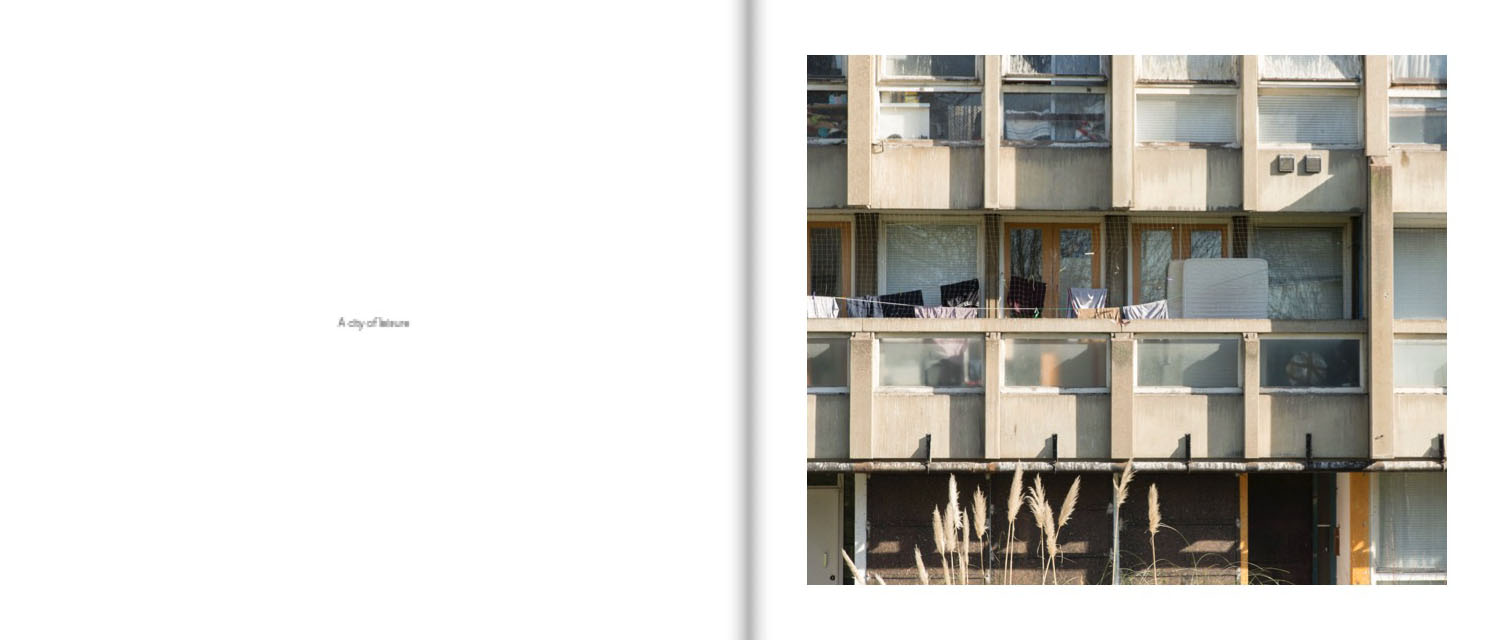

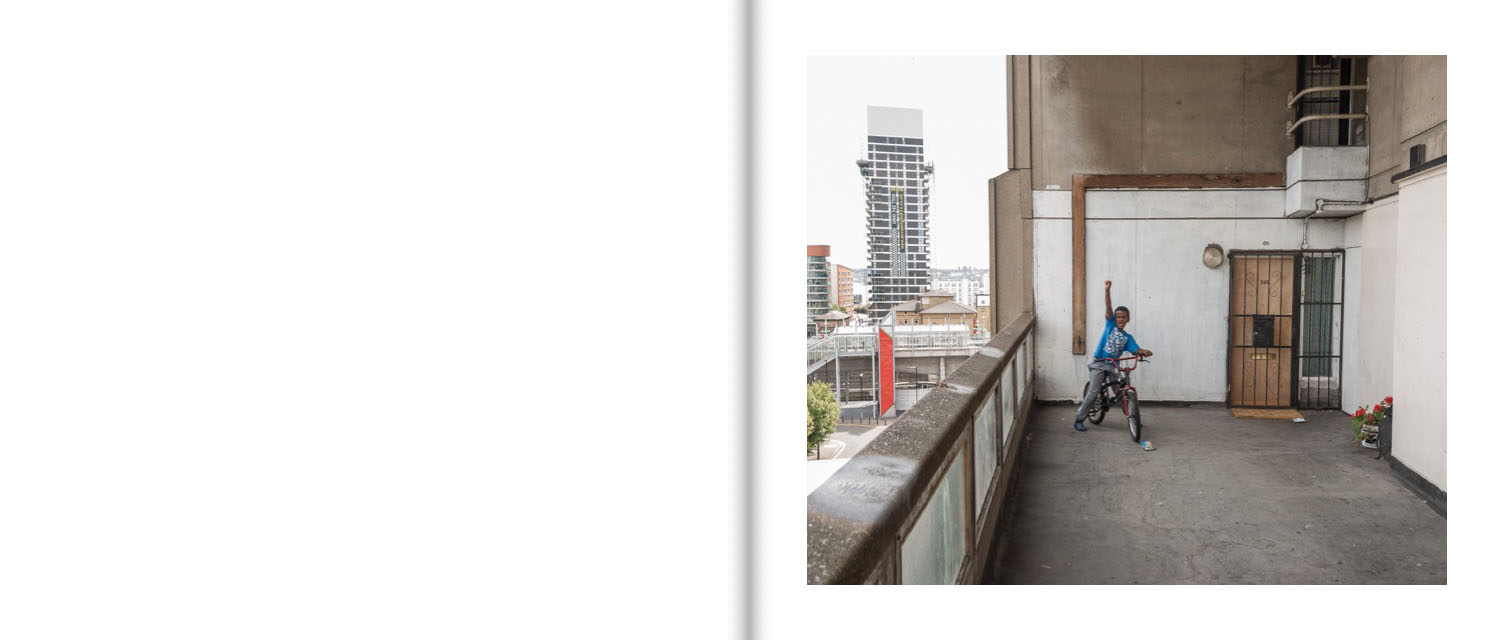

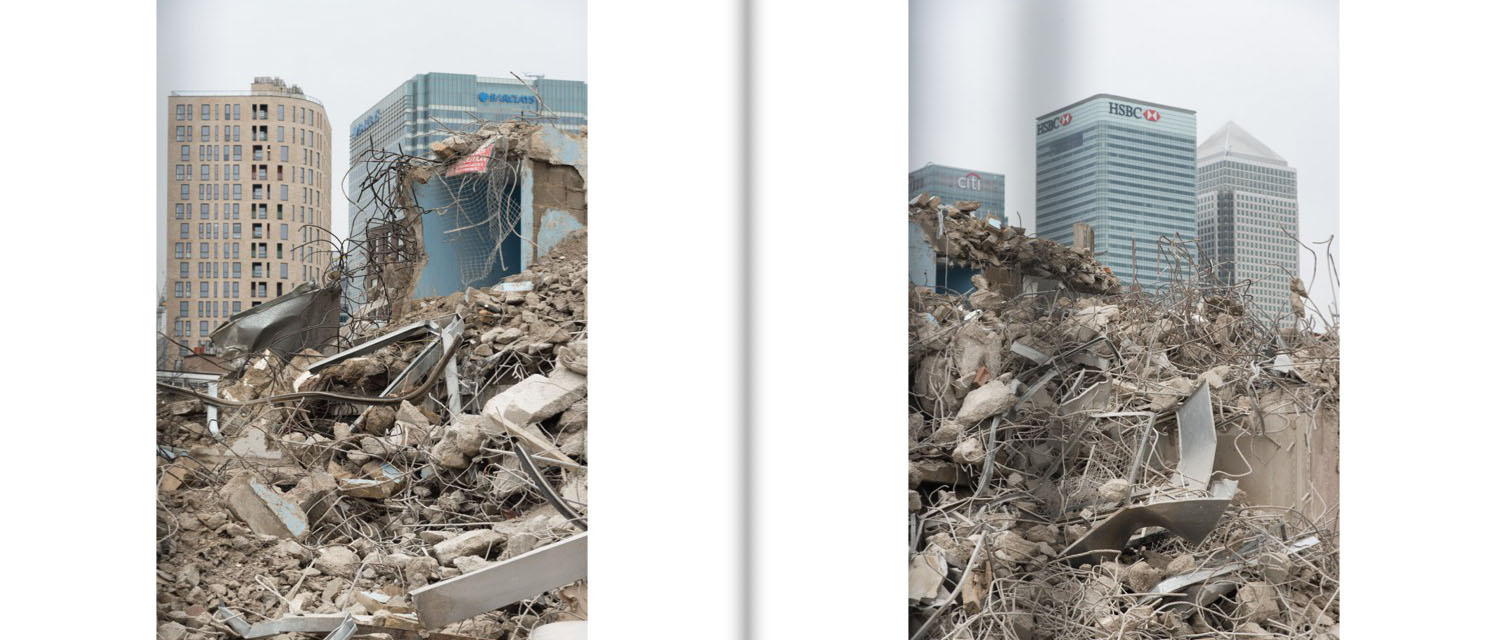

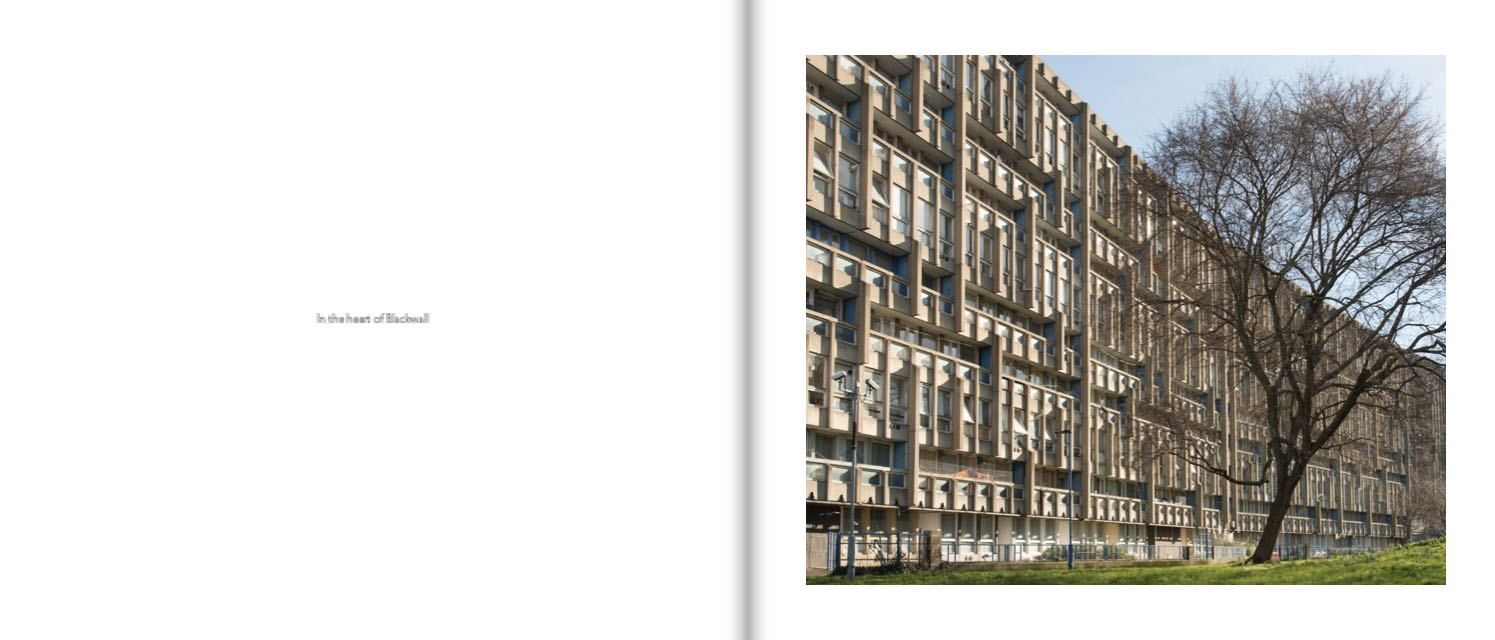

Each time I visited Robin Hood Gardens I felt a mix of melancholy and wonder. The wonder came from the magnificent scale of the two massive blocks, a sense only heightened by their crooked silhouette and fortress-like aspect. The melancholy arose from the estate’s neglect, Tower Hamlets Council having long ceased to fund anything but essential repairs. That feeling increased as residents were rehoused or moved themselves out and steel shutters sealed their former homes. It also came from the sense that these buildings had been designed to address the specific issues of their location, hemmed in by busy roads including the roaring Blackwall Tunnel entrance (see this interview with the Smithsons for more detail: youtu.be/UH5thwHTYNk). Now these buildings were condemned to demolition, to be replaced by high density towers of the most mediocre aspect, which would have no shared spaces outside their front doors for children to play.

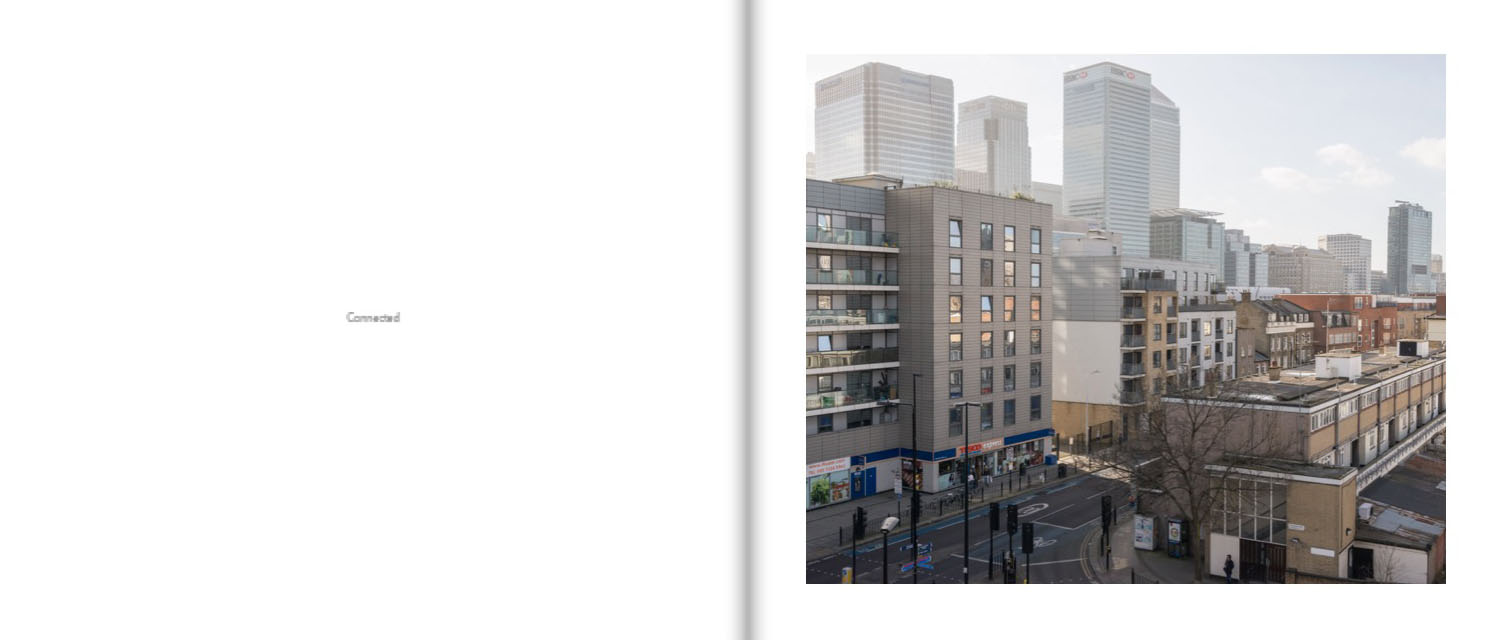

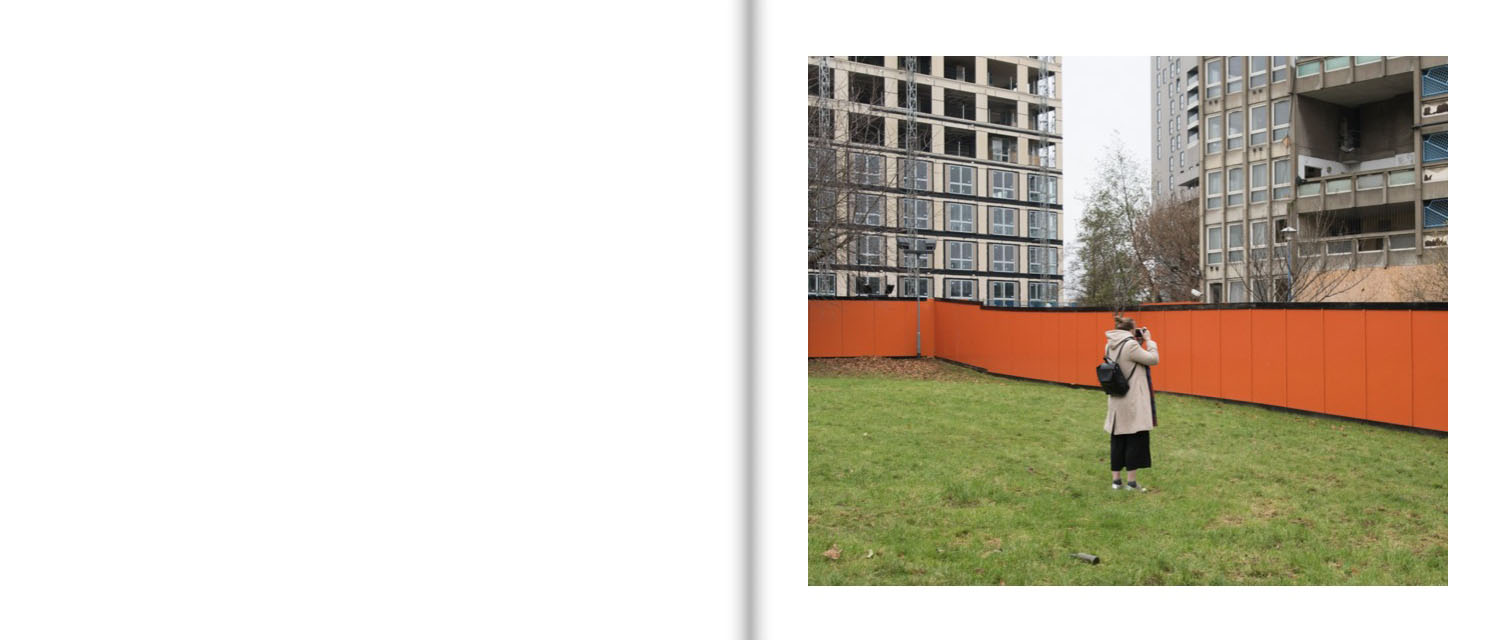

On my visits, I was a stranger intruding onto the raised streets. I walked through the entrance doors tailing residents leaving or entering the blocks. I nodded to people if our eyes met and otherwise tried to be as unobtrusive as possible. I spent time looking out at the roaring Blackwall Tunnel access road or towards Canary Wharf’s towers. I climbed the hill in the central green space and looked across at each of the estate’s blocks, marking the repetition and variety of each flat and balcony. Looking north I could see Erno Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower. On later visits to the estate, I was aware that the Balfron’s tenants had been moved out, then the building was hidden behind sheeting, and it was announced that only those wealthy enough to purchase property would be able to live in the block, allegedly due to the unexpectedly high cost of refurbishment.

This book is a small act of questioning, resistance and memory. Its structure is a deliberate non-linear progression, its slight a-temporality aspires to ridiculous hope, its title and commentary betrays an enduring streak of anger.

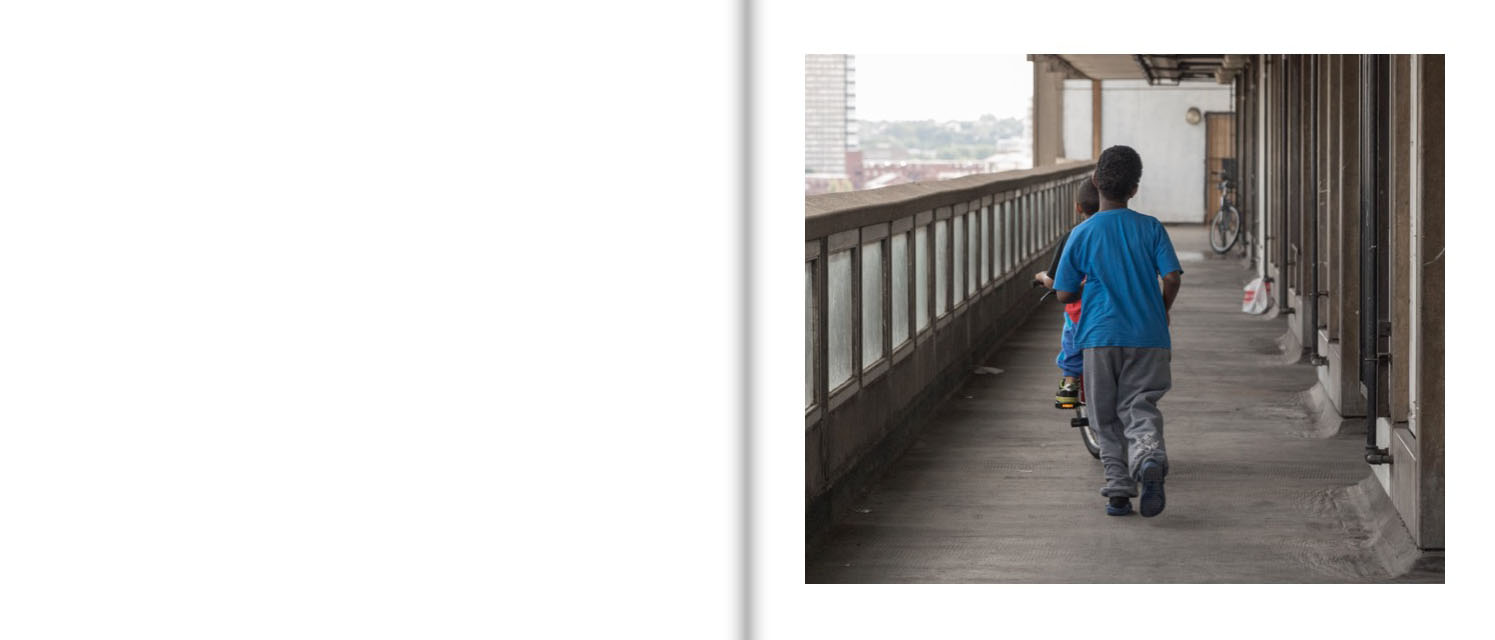

I raced the boy, seen in my photographs, on our bikes on the third floor street of the east block. He was really pleased to beat me! I wish I’d asked his name.

........................................

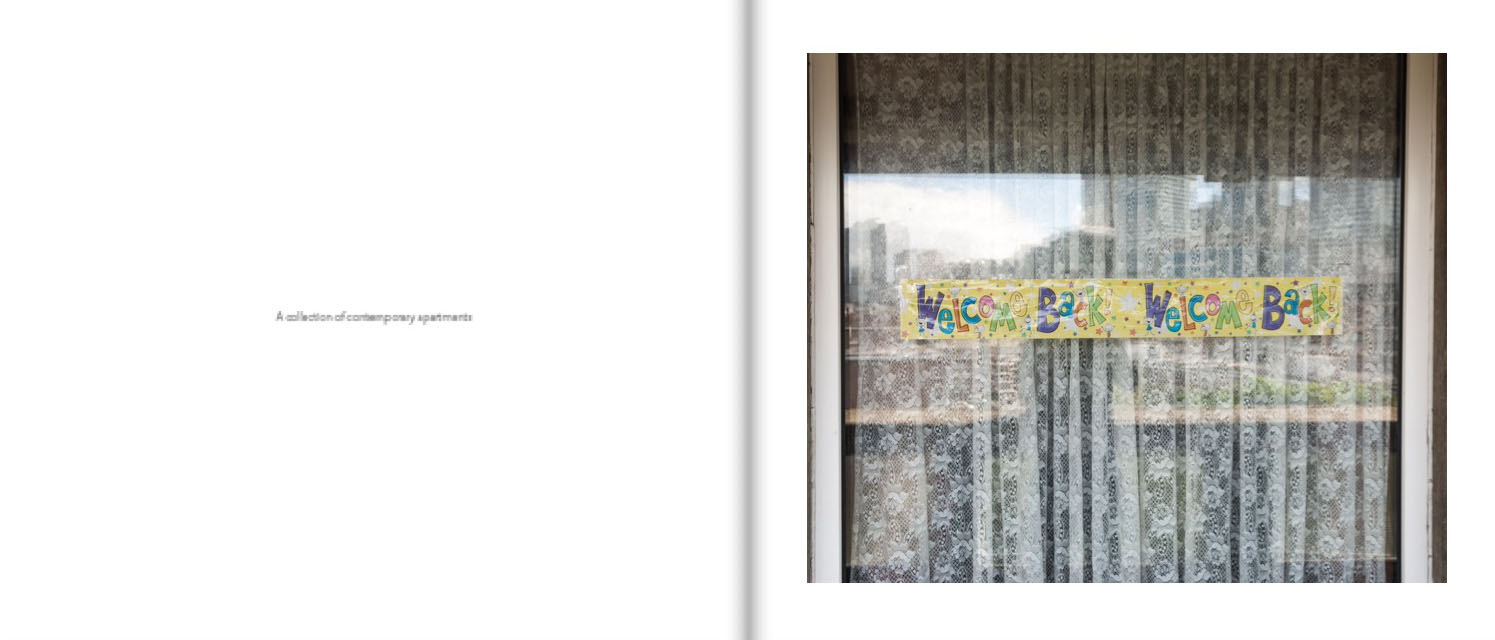

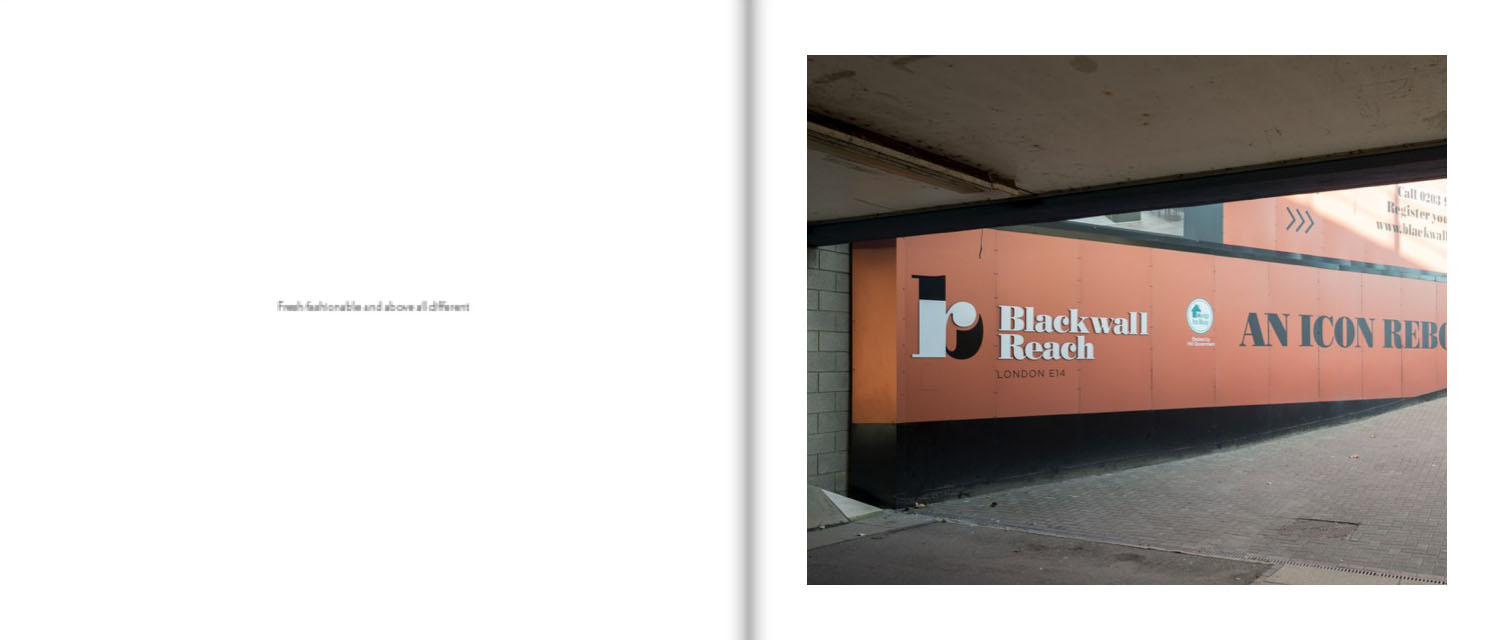

The statements that accompany many of the photographs in this book (e.g. “Welcome to the next big thing in east London urban living”, “An icon reborn”, etc.) are quotations from the Penthouse and Residential Brochures published at www.blackwallreach.co.uk.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.