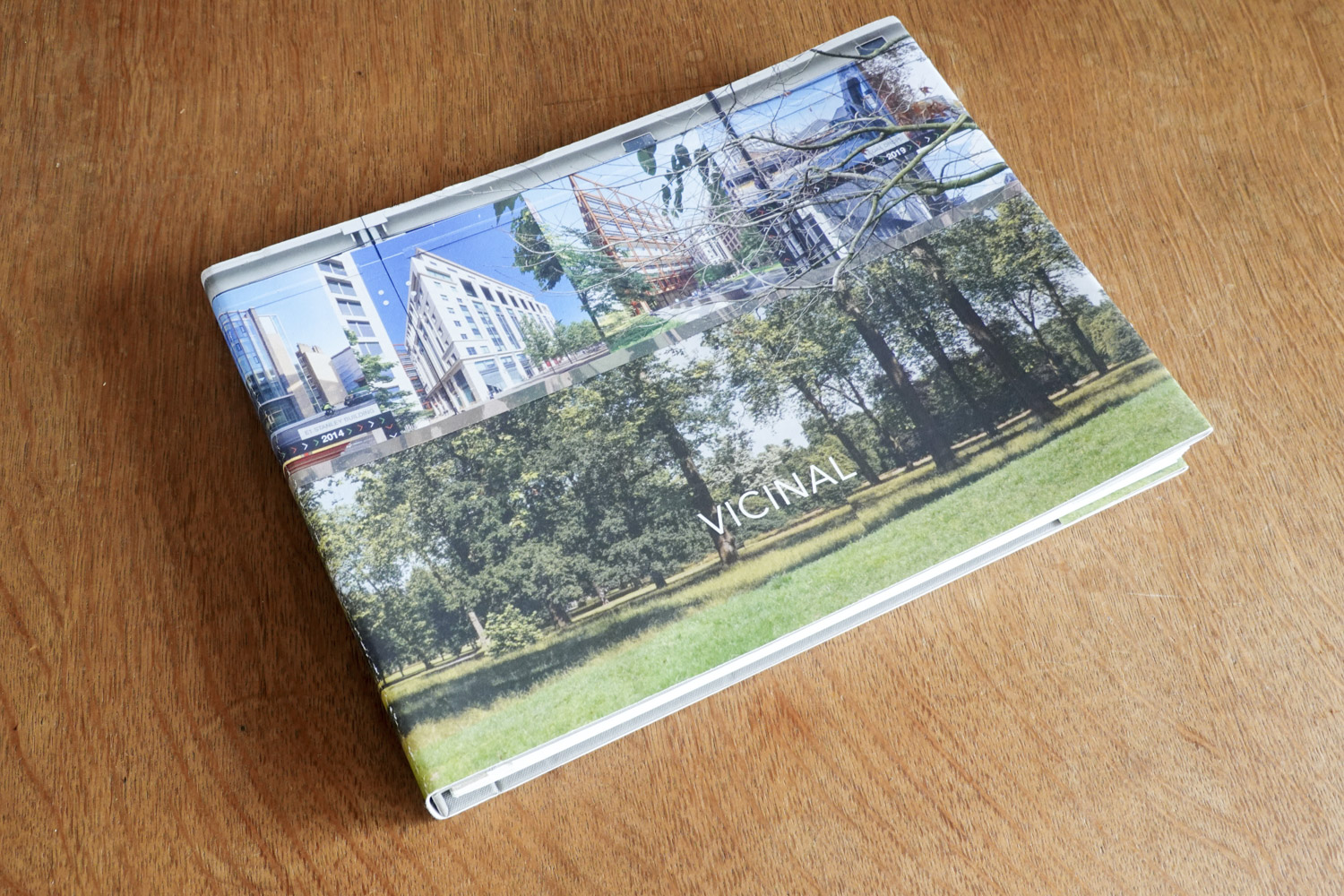

Vicinal

Dimensions: closed w: 29cm, h: 21.6cm; open w: 96cm, h: 21.6cm

Photographs (80): 2011–2020

Book: 2020

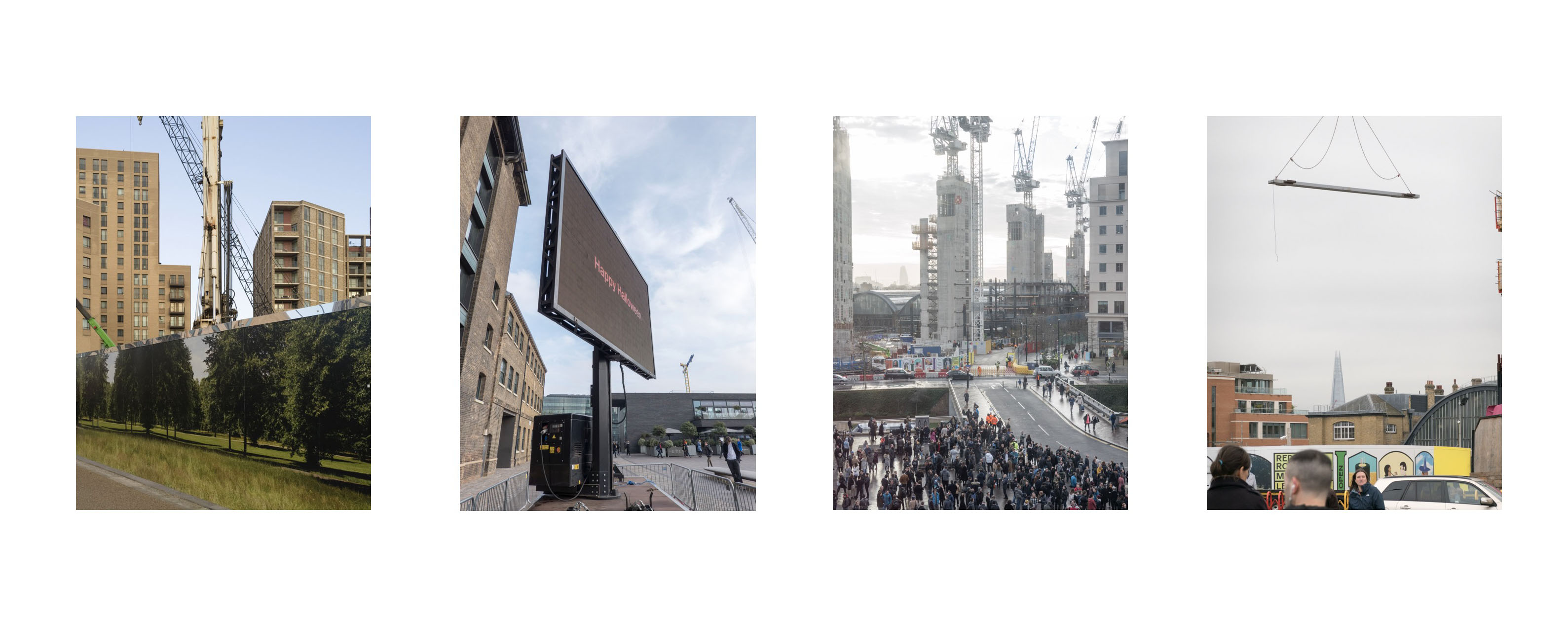

I’ve worked in King’s Cross for nine years, at the art college Central Saint Martins. The college was the first institutional occupant of the area after it moved from a number of sites in central London. The college’s global reputation as an art, fashion and design educator was used by the area’s developers as a ‘cool’ attractor to potential clients. In so doing, it enacted at scale the first stage in the process of gentrification that, in other urban areas of wealthy countries, has seen the dispossession of local residents and businesses. The district, formerly known as the railway lands, had previously been a site of creativity and pleasure-seeking in the 1990s. This was in part a result of the relative freedom from regulation that the area enjoyed. King’s Cross was ‘off the map’ to many because of its reputation for drugs, crime and sex work.

Former Nightlife Editor for Time Out Magazine, Dave Swindells writes in ‘From Bagley’s to Spiritland’ how richly diverse the area was before it was sold for redevelopment. Its history encompassed everything from gay super clubs to fetish nights, roller-discos to the performance art collective Mutoid Waste Company. The area’s occupants were also subject to police harassment and raids.

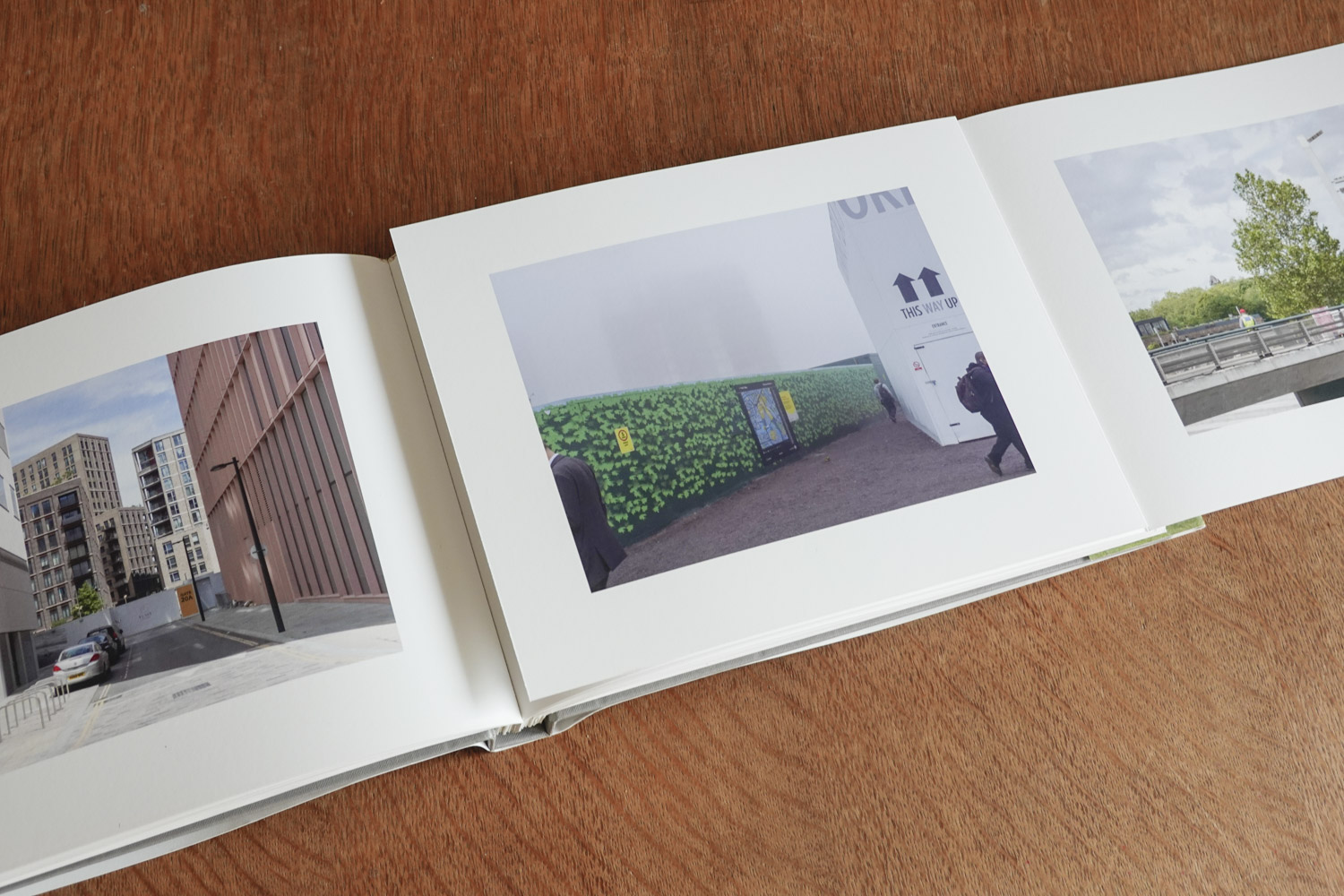

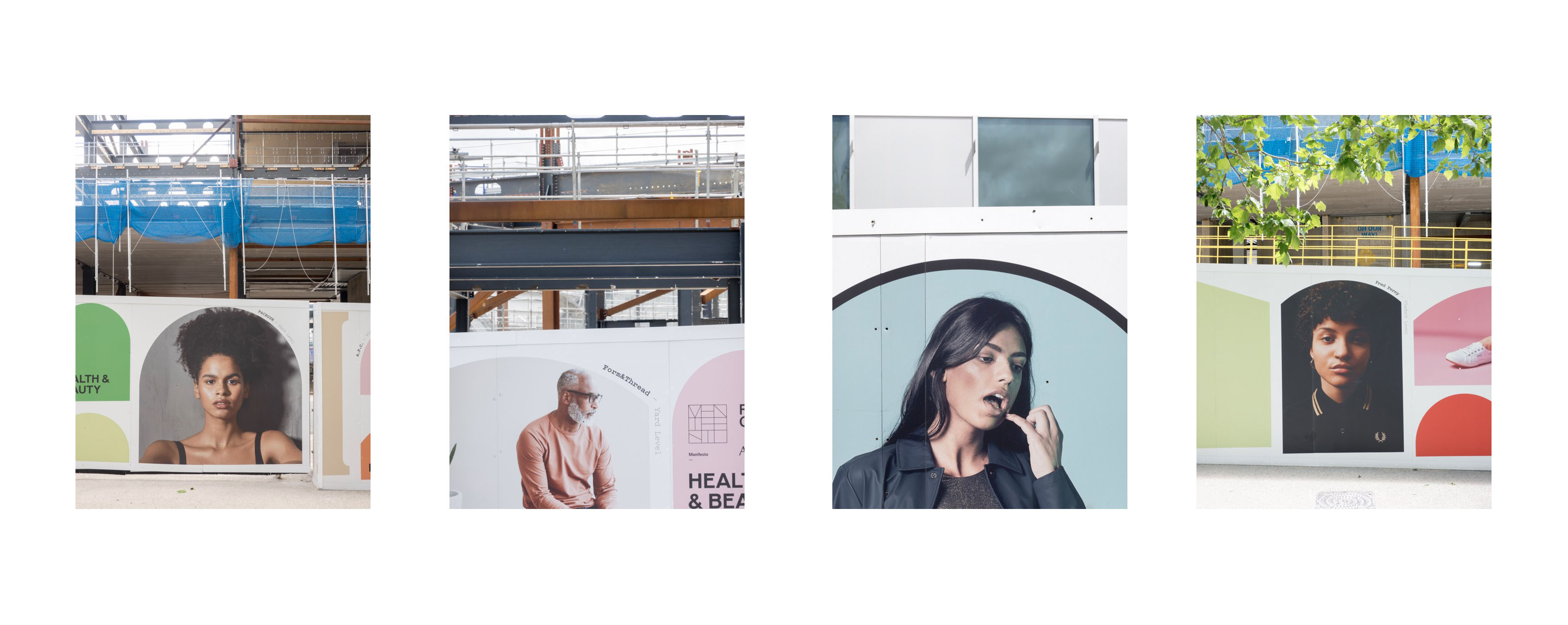

The ghosts of the area’s former freedom are invoked on the Quarter’s construction hoardings which seek to create continuity between the area’s unsanctioned past and its privately regulated present. It’s another example of an all-too familiar charade intended to maximise return on property development. The largest apartments in the Gasholders Building facing Regent’s Canal are currently being offered for in excess of £7million.

The railway lands were also home to a number of small businesses:

“Oh, it certainly wasn’t deserted,” says Allan, “You had Charles Wells the brewery from Bedford over in the Western Transit Shed, truckloads of first editions of newspapers would arrive in the early hours each day, Fortnum & Mason parked all their delivery vans here, Metroline had buses, Pickfords stored antiques, there was a lighting company for big movies, and cement mixers driving in all day to get diesel.”

“We’d have squatters throw illegal raves that took a trip to the high court to have evicted… The regular squatters used to be nice as pie. I got on great with them. We’d say, ‘come on lads, you know you can’t stay here, but see you again same time tomorrow. Just make sure you’re not here when the demolition starts’.”

Allan Horton interviewed in King’s Cross Quarterly, Spring 2020.

At one point in the interview Horton says of the previous occupants that “Everyone helped one another out; there was a lovely little community spirit.” and then goes on to say "What’s nice is to see that the same spirit has returned today. Everybody here talks, it feels like a real town square.”

In conclusion he observes “I came with the land. It was like, you have the land, you have Allan. I was the only one. I felt like one of the buildings, part of the heritage.”

King’s Cross Central is now close to completion. The estate hosts a school for deaf children, an art college, Camden Council’s offices, a library, a public swimming pool, a cinema, open spaces and a community centre. There are no advertisement hoardings except the almost ubiquitous encouragement to visit Coal Drops Yard, the estate’s shopping mall that is struggling to attract clientele to its expensive boutiques.

King’s Cross Central’s development – by corporate entities Argent, a property developer, Hermes Investment Management on behalf of BT Pensioners, and the Australian pension scheme AustralianSuper – has been in close consultation with the local council and is perceived as best in class in the UK.

........................................

The architect of some of the estate’s key buildings, including Coal Drops Yard, is Thomas Heatherwick, best known in the UK for his London bus redesign and unbuilt Garden Bridge, whose company website states:

“The area is a fascinating collision of diverse building types and spaces, of massive railway stations, roads, canals and other infrastructure all layered up to create the most connected point in London.”

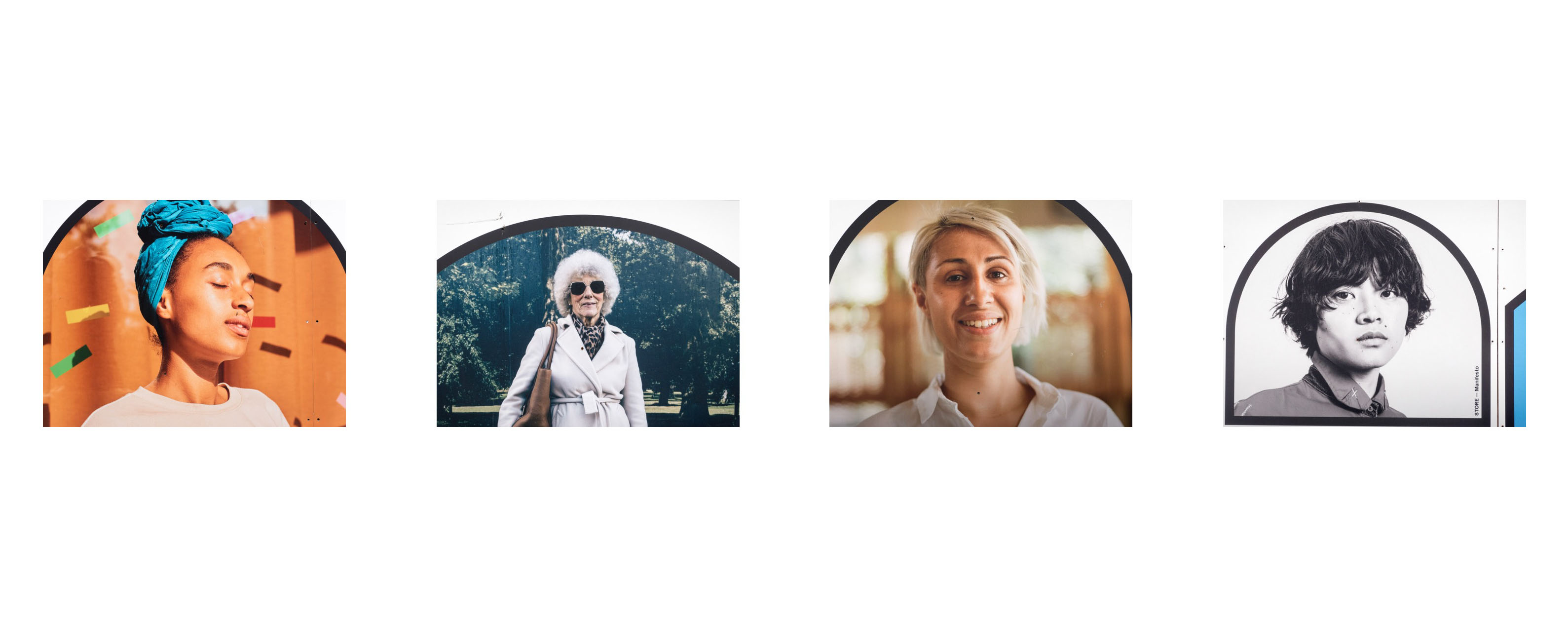

Office workers, shoppers and diners can feel at home here. On sunny summer days, neighbouring communities from the estates sandwiched between the King’s Cross Quarter and gentrified Barnsbury on the other side of Caledonian Road bring their kids to Granary Square’s fountains and play on the grass of Lewis Cubitt Park. They don’t venture further into the estate.

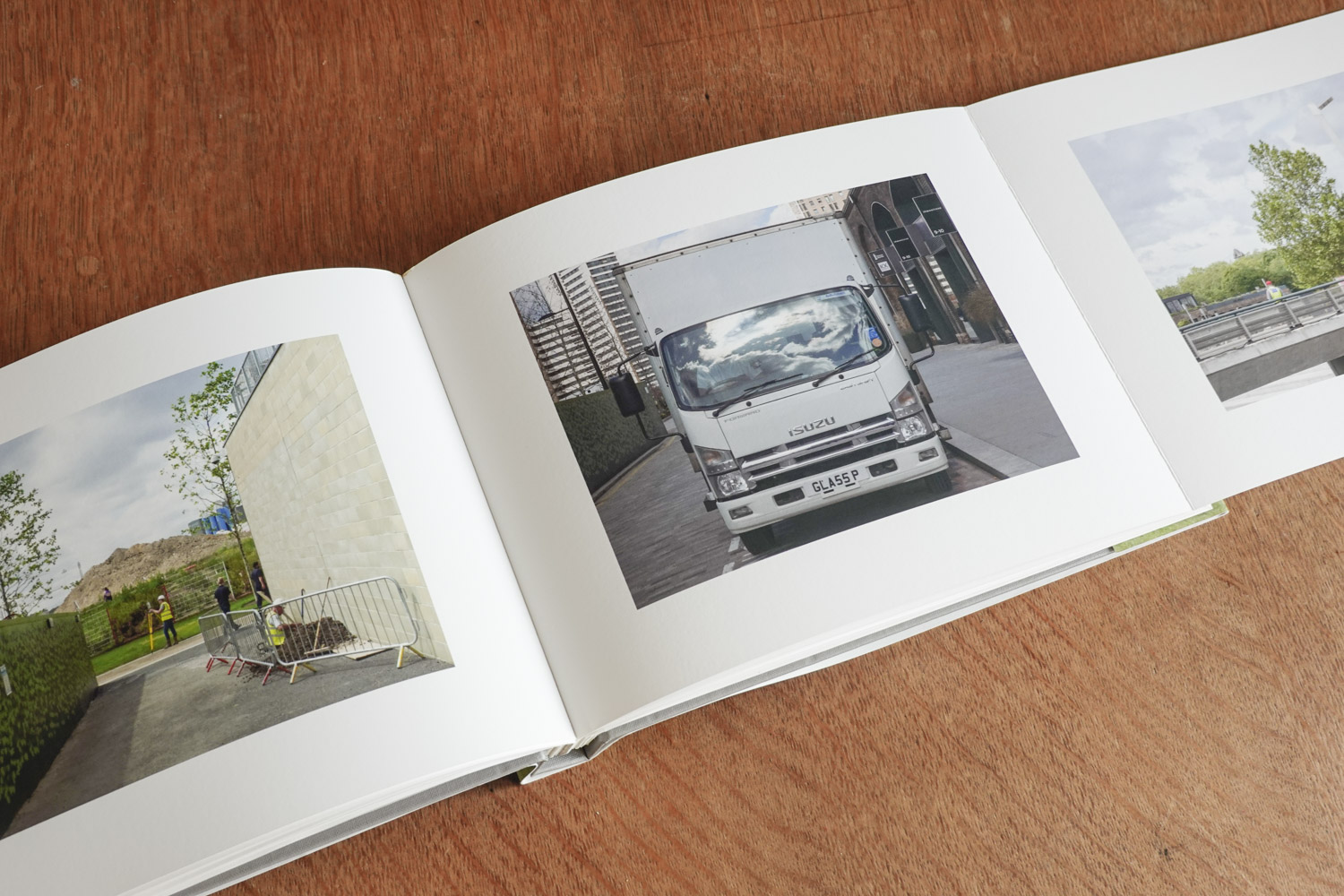

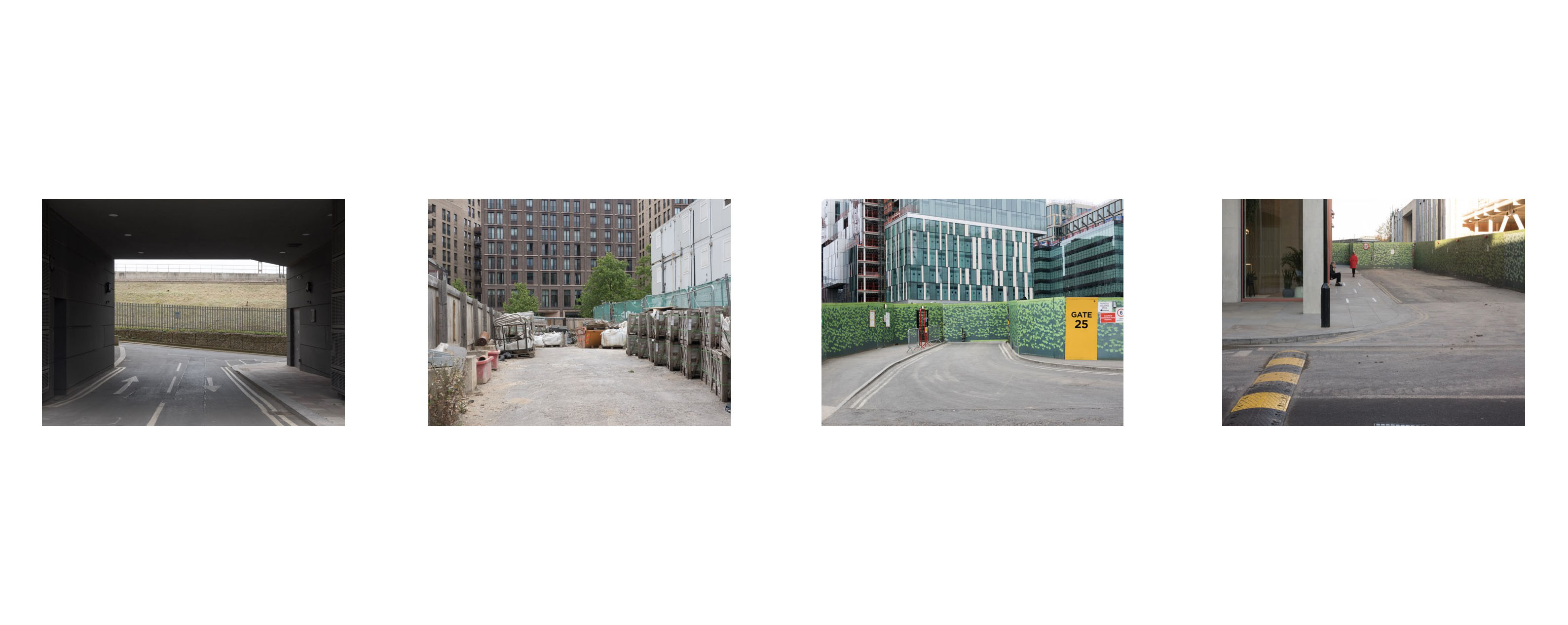

Construction workers are penned in behind hoardings or are seen outside Waitrose at lunchtime. The homeless and the unwell dwell outside King’s Cross station, but are absent further north. If you’re a little shouty or look like you might ask for money, you’ll be approached and escorted out of the area by estate security. Difference, in the form of the art college’s students is celebrated as long as it doesn’t threaten the status quo.

As a privileged white male, dressed for the office, I’m free to move around the estate by the estate’s security, easily identified by their hi-viz vests and red caps. Having been stopped a number of times when using a larger camera in the past, I’ve learnt that if I want to observe and photograph the area outside of work hours, I need to dress smartly. It’s best I also use a small camera that I can hold cupped in my hand to take photographs as unobtrusively as possible.

It may seem a stretch to refer to contemporary Russia in this context, but the similarity is worth noting:

“In Putin’s Russia, anyone who wants to stay in the game (…) knows the necessity of making constant small changes to one’s language and behaviour, of being careful about what one says (…) and what constitutes a violation of the unwritten rules.”

History Will Judge the Complicit, Anne Applebaum, The Atlantic, July/August 2020

One of the striking, though undeclared, aspects of King’s Cross Quarter’s open spaces is that they are highly regulated, but the estate’s owners are not required to make their regulations public. This is a key ‘feature’ of England’s corporatised areas, which are rapidly multiplying as public land is sold to private corporations and government resulting in waning democratic oversight.

It’s a question of verisimilitude. A particular, partial reality is imposed upon the visitor to the King’s Cross Quarter. In this area whose boundaries are invisible yet easily sensed, public access is not an inclusive proposition. Past the railway tracks on York Way, there’s a small homeless camp, unimaginable a few yards to the south on the estate itself. King’s Cross Quarter is a pseudo-public estate, where pseudo is understood as ‘supposed or purporting to be but not really so; false; not genuine’.

........................................

“If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.”

William Hague, then Foreign Secretary defending the practices of GCHQ, 2013

Richard Graham, MP for Gloucester on on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill, 2015

The King’s Cross Quarter has proven to be highly attractive to the key drivers of surveillance capitalism which are increasingly concentrated here. Google has been an occupant of a large building on Pancras Square for some years and its huge new headquarters is being built on King’s Boulevard, a stone’s throw from King’s Cross and St Pancras stations. Facebook’s headquarters is nearing completion on Canal Reach on the northern edge of the estate. Deep Mind, a large artificial intelligence company occupies a number of floors of another building on Handyside Street just above Central Saint Martins. Facial recognition technology was deployed without public permission on the estate, in co-operation with local police, between 2016 and 2018, its stated aim being the apprehension of 'undesirable elements’.

Most of us are highly sensitive to the feeling of a place. We can be at ease in one area then cross a road or turn a corner and find ourselves on our guard and wanting to move on hurriedly as if we, without warning, don’t belong. The estate’s security personnel are are seemingly ever-present and always watchful; there are meticulously curated activities; there’s a strictly regulated level of cleanliness and there are the aforementioned surveillance businesses and facial recognition. The inevitable result is an oppressive sense of constraint.

About the book

The initial idea for the book was to explore the relationship between the King’s Cross Quarter and the neighbouring Caledonian Road community. The impetus came from spending my working day in the former while I’d often walk over to sit in Edward Square, a small park next to Caledonian Road in the summer, or buy a coffee in a cafe when the weather turned colder. Even though I wasn’t a local, I found I enjoyed the feeling of community and life around the Cally Road, especially in relation to the artificiality of the King’s Cross estate.

As I reflected on the photographs I’d taken over the years and took new ones, I found it more and more difficult to integrate or juxtapose an examination of the two areas without effectively stating the obvious. There was no real subtlety or interest in the original idea. However, the more I thought about the King’s Cross Quarter and looked at my photographs, the more I became interested in examining and reflecting on the highly constructed nature of the area. The photographs enabled me to see more clearly why I felt so ill at ease.

The title, Vicinal, is a now little-used word whose meaning ‘neighbouring; adjacent; (of a railway or road) serving a neighbourhood’ alludes to notions of service and raises the question of what or who is being served. The title’s close relationship to the word vicinity also references spatial issues and points to the spread of formerly public, now corporate spaces.

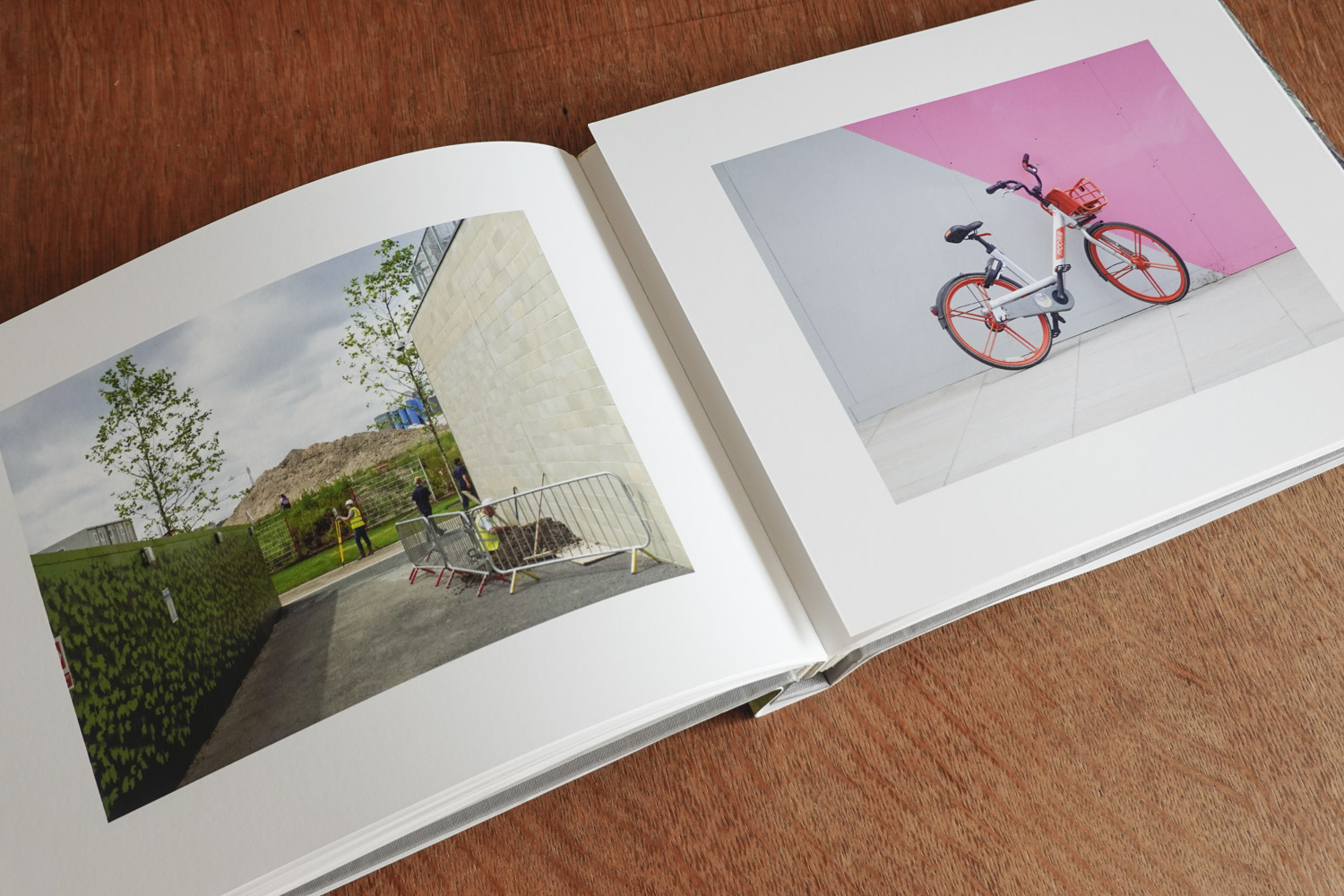

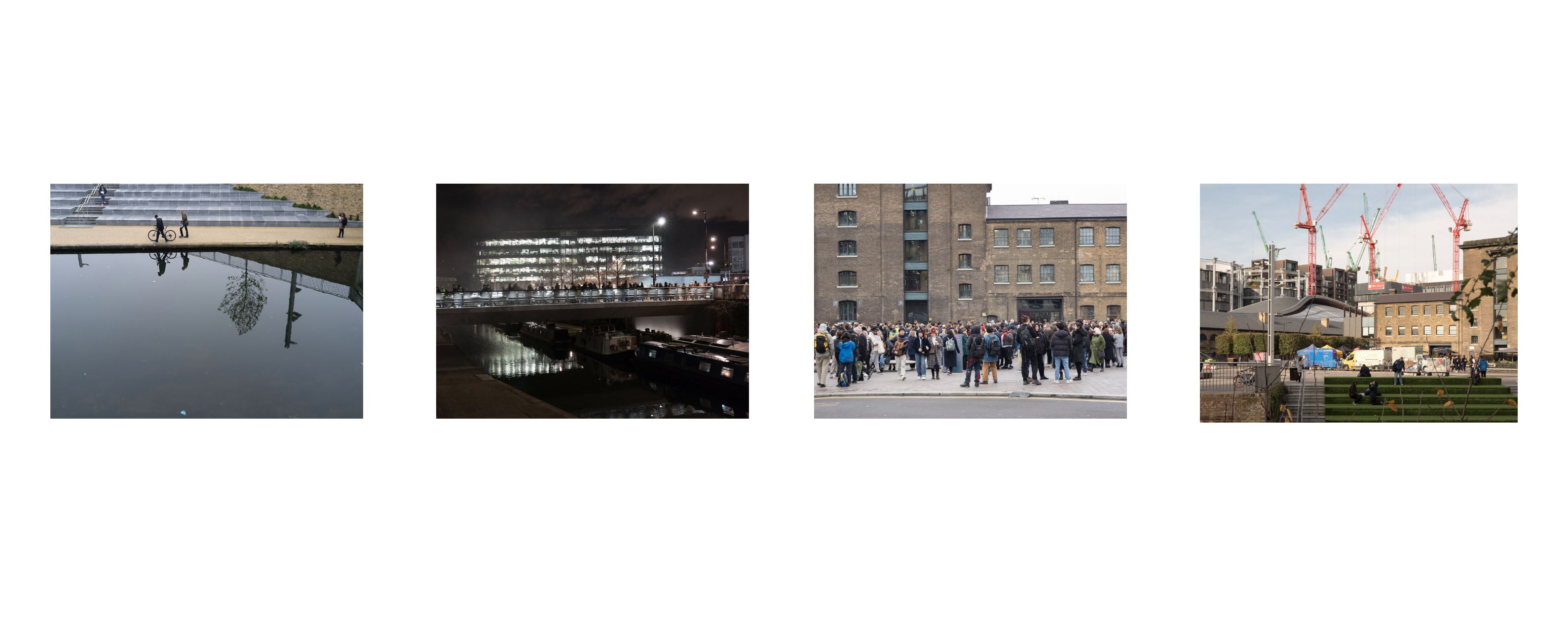

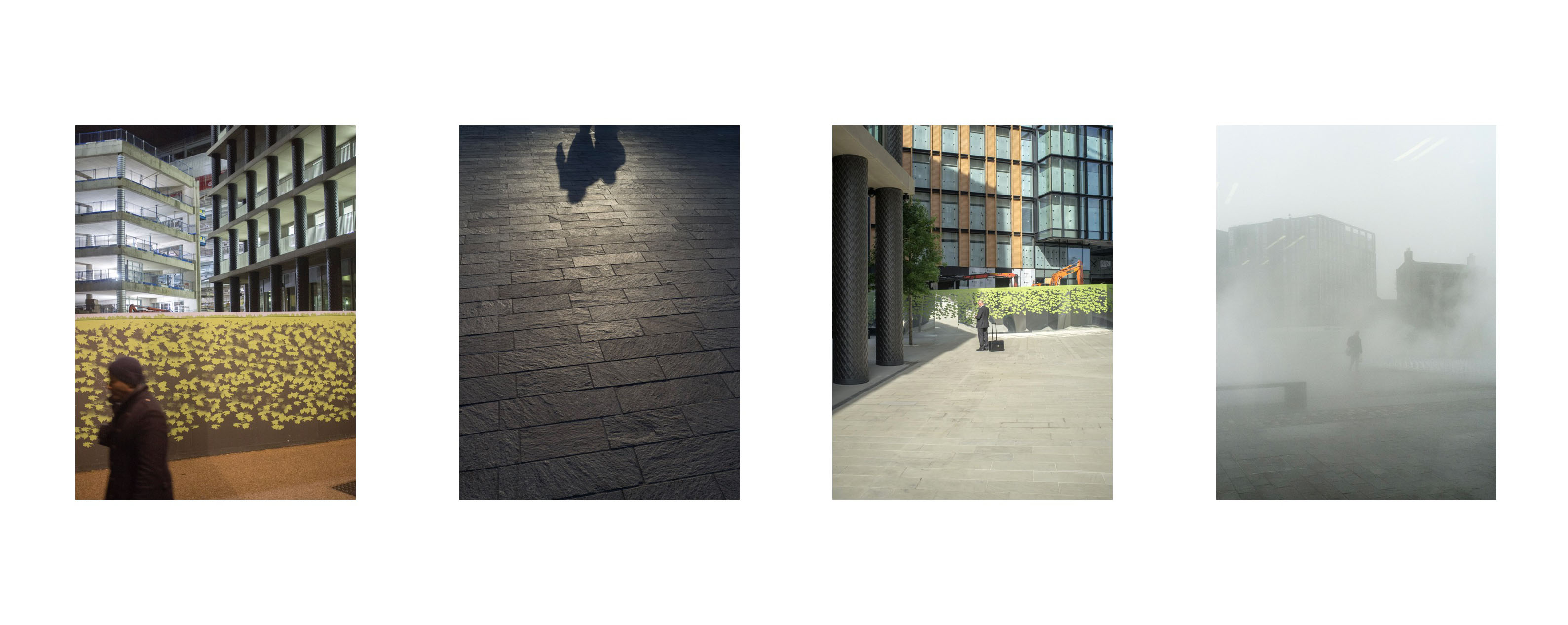

The core unit of Vicinal is a thematically-linked sequence of four images. The book is made up of 20 of those sequences in total and is slightly narrower than A4 in size. However, each spread comprises two pages, or wings, that fold out from each pair of facing pages so the width of the book, when fully extended, is approximately the width of four A4 sheets laid horizontally.

Photographs are printed on both sides of each wing so that each one can be folded inwards or outwards as the reader desires. The effect is a little kaleidoscopic because the folding of the pages creates a surprising amount of variety in terms of image sequences. It’s possible to make arrangements of two, three or four photographs and it is hoped that the reader will discover the flexibility of this arrangement as they move through the book. The format meant that I was unable to control or compose the sequencing outside of the core four image sequence and, once I’d made the book, I was pleased to be able to discover different sequences for myself. This freedom to navigate a structure, however minuscule, is an important aspect of the book and is intended to stand in a critical relation to the constraining nature of Vicinal’s subject matter.

The experience of the book may be quite intense, exhausting even, for the viewer. The continuous series of images, presented without a change in the rigid rhythm, makes for a challenging experience. The structure is deliberate. It reflects the nature of the subject that it documents.

I’ve written this text as part of the process of composing and making Vicinal. I’ve called on nine years of photographs, most of them taken without a particular intention. I didn’t notify the estate of my plans at any point during that time, even once I’d begun to focus my attention in the past year or so.

Vicinal is a critical work. The King’s Cross Quarter’s regulations are only conveyed verbally by its security personnel when its regulations are transgressed. The public cannot reference them online or anywhere across the district’s 67 acres. What, therefore, would the book’s legal status be if it were to be published?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.